Superbly insightful and transportative article written by David Katz detailing the history of and some key defining moments in the story of Compass Point Studio in the Bahamas.

The exceptional quality and particular circumstances of a handful of recording studios have leant them the status of legend. Some have a readily identifiable sound, such as Abbey Road, where the Beatles recorded most of their work, or the 30th Street studio that Columbia Records operated in Manhattan during the 1950s and 1960s, where many outstanding jazz albums were made. In Jamaica, Treasure Isle will forever be associated with rock steady and King Tubby’s as the place where dub was turned into an art form, while Lee Perry’s Black Ark was a hallowed space of aural and spiritual extremes. Other studios have even ended up defining the sounds of an entire era, such as Memphis’ Sun Studio, which gave birth to rock and roll in the 1950s, Stax Records’ Studio A and the Fame studios of Muscle Shoals, Alabama, which were key homes of soul during the turbulent civil rights era of the 1960s, as well as the dual axis of the Record Plant, whose facilities in New York and Hollywood were the ultimate sonic markers of the excesses of the 1970s. The studio to capture the optimism and openness of the early 1980s, in which various adventurous elements of sound and style were harnessed in a futuristic form thoroughly cosmopolitan by definition, was none other than Compass Point, the facility founded by Chris Blackwell some ten miles west of Nassau on the island of New Providence, capital of the Bahamas island chain.

Blackwell is, of course, the founder of Island Records, the adventurous independent label formed in Jamaica in the late 1950s as a vehicle for local talent. After moving his base of operations to the UK when Jamaica gained independence in 1962, Island became the leading overseas distributor of Jamaican product, before Blackwell began finding greater success with experimental rock acts such as Traffic, Jethro Tull and King Crimson. Then, in 1972, after Bob Marley and the Wailers signed to Island, popular music was indelibly changed, a new era dawning through Island’s championship of Marley as the figurehead of the reggae movement.

In 1972, after Bob Marley and the Wailers signed to Island, popular music was indelibly changed, a new era dawning through Island’s championship of Marley as the figurehead of the reggae movement.

As the 1970s progressed, Island continued to nurture the careers of reggae’s most outstanding performers, including Burning Spear, Max Romeo, Lee Perry, Rico Rodriguez and Toots and the Maytals, along with innovative rock artists such as Roxy Music, John Martyn and Emerson, Lake and Palmer. Meanwhile, despite countless successes with a range of material cut at various facilities in Jamaica and at studios Island controlled in London, Blackwell was nurturing a secret dream, namely to open a distinctive studio of his own as home to a unique group of session players that would make music as striking as the rhythm and blues released by Atlantic from the late 1940s, as readily identifiable as that recorded at Motown’s Studio A during the 1960s and early 1970s, as unique and definitive as the work of the Stax or Muscle Shoals players. He thus conceived of Compass Point as a giant blank canvas for audio, a space where music could be made without the distraction of external influence.

“I decided to build a studio in a restful location” Blackwell explains, “and I built it from scratch. A man who worked at the studio at Island’s offices in London was the sound designer and he created a magic room.”

Construction of the 24-track facility took place in 1977, with an MCI 500 series mixing desk and other top-notch equipment installed, initially in one room. High profile recording sessions took place almost from its very inception: in March and April 1978, Talking Heads made the first of many appearances there to record More Songs About Buildings And Food. 1979 began with Dire Straits’ second album, Communique, and immediately after, the Rolling Stones were in residence for a month to work on Tattoo You. In fact, so many mainstream rock acts were booking the place that Blackwell had to build Studio B, a second recording room, to ensure enough time was available for his own projects.

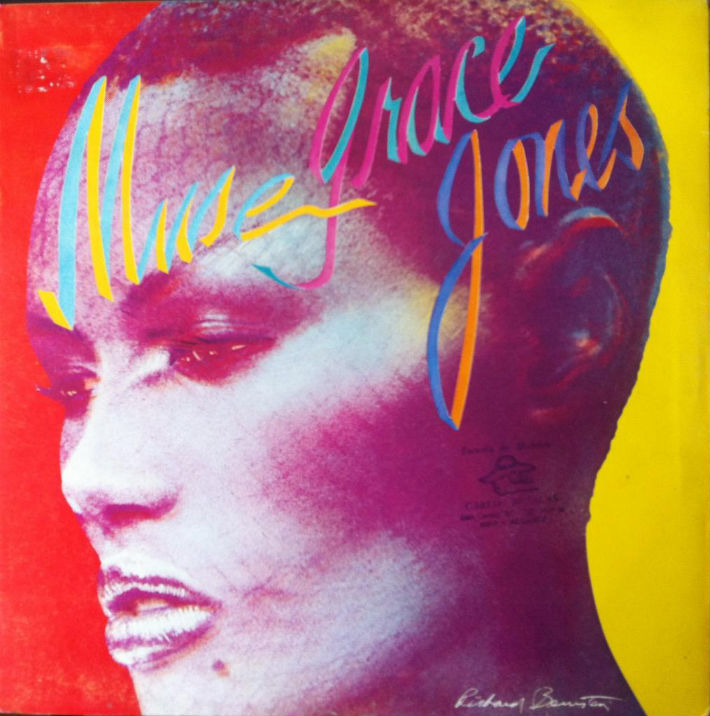

It was towards the end of 1979 that Compass Point really came into its stride, once Blackwell assembled a house band, initially drawn together to work on an album of post-modern cover tunes with Grace Jones, the Jamaican-born preacher’s daughter who became an influential model and disco singer in New York.

“I wanted a new, progressive sounding band,” Blackwell explains. “I wanted a Jamaican rhythm section with an edgy mid range and a brilliant synth player. And I got what I wanted, fortunately.”

The crucial core was comprised of drummer Sly Dunbar and bassist Robbie Shakespeare, then the foremost rhythm section in reggae, long noted for bringing funk and soul elements into their creations, though it is worth pointing out that the duo were not recruited as bandleaders; they were simply valued session players, as was everyone else in what became the studio’s in-house band. “We’d been on tour with Peter Tosh, so we were in New York” remembers Sly, whose nickname came from his adoration of Sly and the Family Stone, “and Chris Blackwell called us up to his apartment. He was saying that he had this Jamaican disco singer, so he gave us some albums she had done before, but we didn’t listen to them… in fact, I haven’t listened to it as yet! He said he’s trying to get a set of musicians together, so we pick Mikey Chung and Sticky, went to Nassau, but nobody knew what we were going to do.”

The studio to capture the optimism and openness of the early 1980s, in which various adventurous elements of sound and style were harnessed in a futuristic form thoroughly cosmopolitan by definition, was none other than Compass Point, the facility founded by Chris Blackwell.

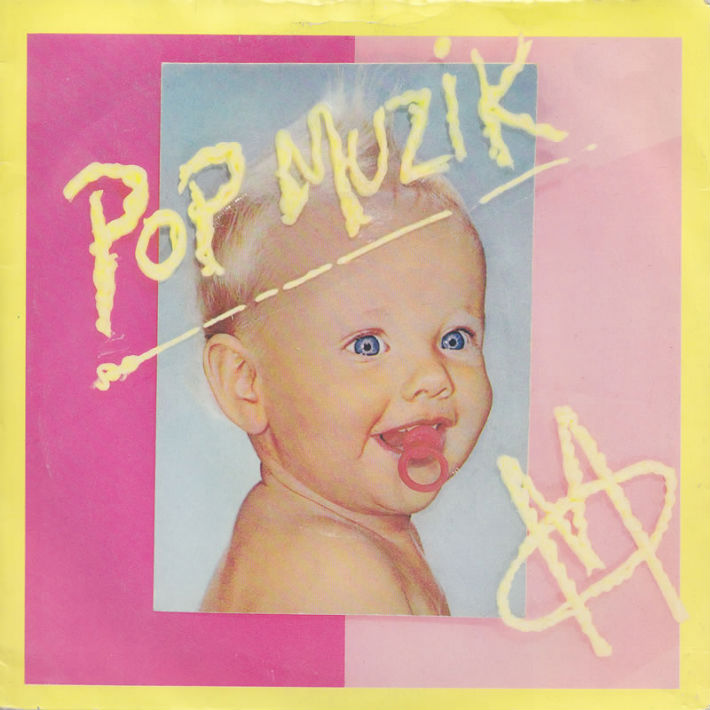

Guitarist Mikey Chung was another stalwart of the reggae scene that played with Sly and Robbie in Peter Tosh’s band, as did percussionist Uziah ‘Sticky’ Thompson, who got his start as a deejay in the ska years, before Lee Perry instructed him to take up percussion. Contrasting this very Jamaican core was guitarist Barry Reynolds and keyboardist Wally Badarou, both based in Europe: Reynolds, a Manchester native that passed through British blues band Blodwyn Pig in the early 1970s, helped revive Marianne Faithful’s career through the Broken English album, recorded for Island in 1979. Badarou was based in Paris, but spent part of his youth in what was then Dahomey, West Africa, where his parents both practiced medicine; his father also served as a government minister before joining the World Health Organisation after the Marxist coup that turned Dahomey into Benin. After playing with various French funk and pop outfits in his youth, Badarou scored a contract with Barclay Records, which led to sessions with Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela, and, perhaps more importantly, to M’s Pop Muzik, a world-wide smash that caught Chris Blackwell’s ear (and led Sly Dunbar to purchase syndrums).

Badarou reveals that he was only vaguely aware of Blackwell when he received a telephone call in October 1979 requesting his presence at Compass Point. “At the time, I knew very little about Island. My ideal world in music was populated with the likes of Stevie Wonder, Herbie Hancock, Weather Report and Earth, Wind and Fire; I liked reggae more as a by-product of American R&B, and as great a groove as Bob Marley’s Natty Dread was, it did not—intellectually—impress me more than Keith Jarrett’s Köln Concert. But one day, Gibson Brothers’ producer Daniel Vangarde told me to expect a call from Chris. I knew I’d heard the name somewhere, but I couldn’t figure out who, what, where and how. The phone call was very gentle and brief, sort of like, ‘Hi Wally, how are you? When can you come over to record?’ Plus a rough figure of salary. No word about Grace, nor about Sly and Robbie. I had a connecting flight in London, and, seated at the back of the plane, I could see this man coming in with a guitar at his shoulder—Barry Reynolds. During the flight, he made me realise we were to be the ‘Old World’ branch going to join people of the ‘New World,’ and that reggae was to be the basis of our forthcoming work, which spelled some kind of anxiety for us. From then on, it’s been a wonderful experience to get to know him, up till today. His kindness has never failed, his mind as articulated as his speech, which always made him the perfect mate to be with in all circumstances. Through the sessions, I learned to appreciate his sober and elegant guitar playing and song writing.”

Also greatly influencing the result was co-producer and engineer Alex Sadkin, who soon became a defining element of the Compass Point sound. Universally praised for his professionalism and openness, Sadkin got his start as a sax player in a Floridian jazz band, Los Olas Brass (Jaco Pastorius was also a member) and wound up as mastering engineer at Miami’s famed Criteria studio, where he worked on Neil Young’s Long May You Run and Bob Marley’s Rastaman Vibration. Sadkin’s precision is as famous as his kindness, his attention to detail and gentlemanly nature often resulting in exceptional performances from the artists he worked with.

“I think Alex really brought a lot to the plate” says Mikey Chung. “He is one of the best engineers I have worked with, because of his ideas and concepts, and how meticulous he was with getting Sly’s drum sound—he’d work for hours getting that snare drum to sound that crisp. He’d be very experimental too. And I think the outcome, when you hear Grace Jones, you can hear it.”

“Alex Sadkin was a perfectionist” stresses Chris Blackwell. “He was a dream for me to work with.”

“He was detailed” recalls Sadkin’s understudy, Steven Stanley, the young Jamaican that Chris Blackwell installed as in-house engineer in March 1978, “like when he sets up his drums, he take all four hours, something I’ve never seen anyone do before.”

“I learned from Alex the value of the ‘rough mix’” adds Wally Badarou. “Everything sounded near finished at all times; he never stopped polishing the sounds on each listening pass. So when I was to do overdubs, I always knew precisely what would be the end result of each take, which allowed me to be very specific and sober on everything I added. Alex’s work was inevitably very slow, but judging by how his recordings and mixings are now celebrated worldwide, he clearly had time on his side.”

According to Badarou, the sessions had a pitifully slow and chaotic start. “Upon arrival, Barry and I were put into a big house, but there was no one around but us for days—no Grace, no Chris, no Sly, no Robbie. Then they all came up, two by two. Alex Sadkin finally told us that Grace had been somewhere in town; one day, as we were mucking about in the recording area, she finally showed up. A couple of drum sound adjustments later, I could see someone at the console, looking very relaxed, whilst everyone acted very respectfully towards him; Grace just yelled, ‘Hi, Chris!’ and that’s how I knew who that was. But by that time, I was so infuriated by the very relaxed pace of the events that I don’t recall having been formally introduced to him.”

As would often be the case at Compass Point, spontaneity was a key element of these sessions, which would meld the sensual contours of funk and dub with the occasional antiseptic gloss of disco and the jagged edges of new wave to yield a highly futuristic blend; additionally, Jones’ Jamaican heritage helped her bond with the core of the team, while her striking image, which had recently been restructured by art director and paramour, Jean-Paul Goude, was another defining factor of the music made.

“In the studio, there was big posters of her with a shaved head” Sly explains, “so when you’re playing, you keep looking at the image; it’s like you’re making a movie score, looking at part of the picture. As a person, I think she was cool; I don’t know if it’s because she was almost Jamaican, so she feel very relaxed and comfortable, cause we can relate to her and she can relate to us—there’s respect for everybody there.”

“Chris make we hear some Grace Jones album” Robbie continues, “show us how she looks, says he wants music made to that image. We go Nassau and started building tracks for her and she wanted us to rehearse before, but we said, ‘No man, fuck that! We just run the song.’ That’s the way we usually work, so the old-fashioned way of rehearsing, that’s a joke, because when you rehearse and you get a feel, by the time you come back to the studio, you get a different feel.”

“I played acoustic piano on Warm Leatherette and Chris was thrilled, but the whole thing sounded bizarre to me” adds Wally Badarou. “I just didn’t get it, and I didn’t care much, so concerned was I by the logistics of our accommodations, rather eager to be done with the job and get back home for more serious projects. Only when we did Private Life did I start to realise the potential of what was going on, but did not fully understand, and neither did the rest of the team. Only Chris knew. He used to say repeatedly, ‘This is the best band I’ve ever heard.’ But I thought he was just being nice to us.”

Thus, on Warm Leatherette and subsequent albums Night Clubbing and Living My Life, the Compass Point All Stars did more than just bring Grace Jones to the top of the charts; indeed, their futuristic fusion changed the course of disco as well as pop music in general, by making the first more inclusive and the latter more adventurous. The twelve-inch version of My Jamaican Guy, taken from the Living My Life sessions, shows off the tightly wound dubwise groove supplied by the All Stars; Sly notes that Grace’s vocal pacing mirrors aspects of the Jamaican folk form called mento, while Wally Badarou says his keyboard hook was taken from an older composition put together some years previously.

“The Grace Jones sessions were so enjoyable, partly because I had the band all playing live” Chris Blackwell emphasises, “and I would have three or four musicians all overdubbing at the same time. It was ‘lightning in a bottle’ and it was then that I thought about them as a house band, like with Stax and Motown.”

Meanwhile, after the initial set of sessions that produced Warm Leatherette, quirky new wave act the B-52s came to Compass Point to record their debut album, after Talking Heads and their manager, Gary Kurfirst, recommended the group to Chris Blackwell. Then Aussie rockers ACDC cut Back In Black, hailed by many as one of the greatest hard rock albums of all time, before a fragile and fractious Talking Heads returned to Compass Point in May 1980 to begin working on Remain In Light, which many rate as their finest release. The disorder of these sessions is legendary, with co-producer Brian Eno and lead singer David Byrne initially cold-shouldering each other due to an earlier unspecified falling out while working on My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts in San Francisco; engineer Rhett Davies quit Remain In Light after just three days, leaving Eno, Steven Stanley and hired hand Dave Jerden to keep the mix intact as the band fleshed out abstract rhythms during chaotic jam sessions. The album was later completed at Sigma Sound studio in New York with guitarist Adrian Belew and backing singer Nona Hendryx, pointing the way towards the expanded band that subsequently rocked audiences on tour. Born Under Punches, the driving track that opened this magnificent album, captured the Heads at their most tense and dramatic, with Byrne’s eerie lines about the hands of a “government man” being strangely contrasted by an off-kilter chorus of “the heat goes on…” apparently borrowed from the headline of a New York tabloid.

In an era when punk and disco seemed at polar opposites, New York’s No Wave movement attempted to blur perceived boundaries between the two styles by drawing from disparate elements to avoid stereotypical characterization, and Compass Point became associated with the movement thanks to Island’s links with ZE Records, the pioneering label that became its bulwark. Michael Zilkha, an Oxford-educated publisher whose immense wealth stemmed from the Mothercare retail chain, and his friend, Michel Esteban, owner of Parisian punk shop Harry Cover and founder of the magazine Rock News, formed ZE when Zilkha’s future wife, Cristina Monet-Palachi, a Harvard graduate who was then arts critic at the Village Voice, kick-started her singing career by recording a punk-disco satire produced by John Cale; the single caught Chris Blackwell’s attention, so he arranged to distribute ZE’s releases through Island.

Esteban’s girlfriend, Lizzy Mercier Descloux, was another early fuser of punk and disco that was hailed as a Patti Smith protégé when the pair left Paris for New York. After the underground success of her debut, Press Color, Descloux and her backing band reached Compass Point in October 1980 to record the Mambo Nassau album with Steven Stanley and Wally Badarou; like her debut, it drew on a number of genres, including contemporary African music, as made clear by the driving, scat-vocal, dub-funk track, Lady O K’pele, which, like the rest of the album, navigated adventurous, if somewhat hazy, directions.

“It became increasingly interesting as we went into production” says Badarou. “I still can’t tell in precise words what it is she or we were looking for, but there was undeniable complicity; I can’t speak much about the musical value of the end result, but we enjoyed the process. I guess it had more to do with posture or gesture than musicality; maybe another album would have made things clearer.”

What do you get from the following ingredients? An itinerant non-musician playing a keyboard upside down, three singing sisters not necessarily trained in harmony, an inverted bass line and clandestine handclaps. The answer, obviously, Genius Of Love, magnum opus of the Tom Tom Club.

Cristina also travelled to Compass Point in the same era, the intention being that her sophomore album would be produced by Robert Palmer, the soul-influenced English rock singer who was often around as he had long been based in one of the properties at the Tip Top apartment complex that was situated in the hillside behind the studio but, for reasons that remain unclear, that particular project was shelved. The demo version of the faux-country lament, You Rented A Space, featuring production and instrumentation by Palmer, is thus a tantalising glimpse of what might have been if the album begun at Compass Point in 1981 had managed to reach full fruition.

What do you get from the following ingredients? An itinerant non-musician playing a keyboard upside down, three singing sisters not necessarily trained in harmony, an inverted bass line and clandestine handclaps. The answer, obviously, is a hit record that caused a sensation with diverse audiences internationally: Genius Of Love, magnum opus of the Tom Tom Club. Though the original Talking Heads would remain intact for another few years, in early 1981, it seemed the group would not survive the internal pressures that were forcing its members apart: David Byrne and guitarist Jerry Harrison were recording solo albums, so the husband and wife team of drummer Chris Frantz and bassist Tina Weymouth contemplated something of their own, though both were adamant that the work would not be for a ‘solo album’… A project with Garland Jeffries producing for Sire Records was mooted, but Chris and Tina preferred to work with Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry for Island so, after meeting with Perry in New York and verbally securing his participation, the pair decamped to Nassau, but Scratch never turned up as planned. The pair thus began working with Steven Stanley at Compass Point’s Studio B in the spring of 1981.

“We were tossing around ideas” Chris Frantz remembers, “and we got a very poor offer from Sire. Chris Blackwell, on the other hand, gave us a very interesting offer, which was, ‘You go into my studio.’ We’d already been in and done two records at Compass Point at the time, and we’d also introduced (Blackwell) to the B-52s, which I think he appreciated quite a bit.”

“(Blackwell) was asking Chris what cover songs Grace Jones might do” adds Tina Weymouth, “and then he invited us to become part of the artists’ community that he was starting to form around Compass Point. Steven Stanley was writing a track called Tropical Depression, which I really related to, because it had rhythm and melody, the way that Chris and I loved Kraftwerk. So we said, ‘Can we work with this kid?’ In three days, we started three tracks: Wordy Rappinghood, Genius Of Love and Lorelei. We didn’t know what to write and I didn’t want to sing a thing, like, let’s just let it be instrumental. But Chris and Steven Stanley were saying, ‘No, you’ve got to sing!’ I said, ‘What do you mean I have to sing?! I’m a bass player.’”

Tina eventually consented to voice the funky beats that had been laid down with Stanley in loose sessions, and was later joined by her sisters Lani and Laura on backing vocals (with Sly and Robbie eventually borrowed from a Grace Jones session to provide some handclaps). The most outstanding track to emerge from these sessions was Genius Of Love, whose funky root was somewhat inspired by Zapp’s club classic, More Bounce To The Ounce, while Tina’s dreamy lyrics formed an oblique love song to her beau and saluted a number of music heroes from black America and Jamaica.

Steven Stanley played a big part in the song’s construction, which was the result of a complex composite process. It is worth noting that Stanley’s career began almost by accident: after his high school teacher noticed him fooling around on a piano in 1975, he brought Stanley to Aquarius Studio to train as an apprentice, where he instantly fell in love with the mixing console; he thus approached Genius Of Love with a similar sense of random openness to that which brought him to his craft.

“One day (Chris Frantz) say he want a groove like More Bounce To The Ounce, with the double-beat first” Stanley explains, “so I use the AMS delay, 150 mili-second. Then Tina came with the bass and we invert the ‘More Bounce To The Ounce’ bass line… the next morning, they went ahead and write the lyrics — I think they used to read a lot of novels, that’s how they always have good lyrics.”

As Tom Tom Club were getting their act together, cockney-styled singer Ian Dury and his longstanding song-writing partner, Chaz Jankel appeared in Studio A to record Lord Upminster with Sly and Robbie.

Stanley also played the song’s idiosyncratic keyboard line, which Chris Frantz reveals was based on a part Frantz played on a demo version of the song. “I always try to play keyboards” says Stanley, “but I don’t like to play when anyone’s around, because sometimes I do strange things—turn the keyboard backwards, so that I could play comfortable, with one finger.”

“When we started the project, I used to play and sing folk guitar” adds Tina, “and I love the Beatles, the Beach Boys, and the Everly Brothers, so I’m thinking what would be really nice is to get some harmony in there.” Thus, she invited her sisters to join her in a unitary chorus, intricately arranged by Steven Stanley.

This unusual mix yielded surprisingly spectacular results, the song’s salutation of such high ranking funk and soul stars as James Brown, Smokey Robinson and Hamilton Bohannon ensuring popularity with black America, as well as with the new wave crowd already enamoured with Talking Heads. Indeed, the success of the song on the resultant Tom Tom Club album allowed Chris and Tina to secure a 99-year lease on one of the Tip Top apartments. But why did the song include the cryptic line, “We went insane when we took cocaine…?

“Those were the people that we were listening to when we were going through our courtship” says Tina of the artists named on the disc “and at that time, I was trying to get Chris to quit cocaine. With the (Talking Heads) big band, Busta ‘Cherry’ Jones and Bernie Worrell were really into it, and Chris was always trying to keep up; I hated it, so that song was my love song to Chris.”

As Tom Tom Club were getting their act together, cockney-styled singer Ian Dury and his longstanding song-writing partner, Chaz Jankel (both pictured right at the top of the article) appeared in Studio A to record Lord Upminster with Sly and Robbie and keyboardist Tyrone Downey, a regular member of Bob Marley’s Wailers for much of the mid-1970s. Although very little had been prepared before Dury and Jankel arrived in Nassau (because, according to Jankel, “Ian was getting a little bit blasé, and thought, ‘I’ll wing it when I get out there’”), they quickly started bashing out ideas for a controversial number called Spasticus Autisticus, a driving piece of funky post-punk in which Dury lampooned attitudes towards the disabled, refashioning Kirk Douglas’ cinematic portrayal of Spartacus to suit his own purposes.

“In a way, it was Ian’s swansong” Jankel explains, “it stayed in the set for every single gig he ever did from that point onwards. If I had to say, what one song summed up Ian, I would say Spasticus Autisticus, because of what he said in it. He lived and breathed that song. It was all about Ian not wanting people’s charity.”

“Everybody was giving jokes,” says Stanley, “especially Ian Dury and Chaz Jankel. A lot of the music was spontaneous; everybody was feeding off each other.”

Though given a partial ban in Britain due to its subject matter, Spasticus Autisticus became a top 40 hit in America, where it served as a dance club floor-filler, courtesy of the fat rhythm provided by Sly and Robbie, as is particularly apparent on the dub version that appeared on the B-side of the original 12-inch single. Jankel says that, at the recording session that yielded this track, “You could hear the bass playing through the floor” and notes that Steven Stanley was a big part of the overall sound. “I think he’s an absolute genius, he’s got a very personalised vision of sound, started his own path. He’s also a total eccentric and very quick with his tongue; he’s one of the few people I’ve ever met that could actually silence Ian.”

The fact that Lord Upminster coincided with the Tom Tom Club sessions yielded other unexpected connections: not only did Jankel’s sister Annabel direct the Genius Of Love video with her partner, Rocky, but Jankel himself wound up in a romantic relationship with Laura Weymouth, rendered problematic due to its trans-Atlantic nature. Nevertheless, their romance inspired some of the forlorn tracks on Chazablanca, the solo album Jankel recorded at Compass Point the following year.

“The problem was that she lived in New York, I lived in London, and neither of us really wanted to give up our home town” he explains. “So some of the songs on the album were reflecting the fact that we couldn’t be together but, ironically, I invited her to work on the album with me. In a way, it was natural for it to happen, but I was singing about the pain of not being with her, the difficulties of pursuing a relationship under those circumstances.”

Such sentiment is apparent on Whisper, which features Laura singing in tandem with Chaz. “She offered up the lyric, ‘When there’s shouting all around, it takes a whisper to be heard,’ and we built it up around that…” he recalls. “I brought drummer Jamie Laine from London with me, and (assistant engineer and local funk musician) Kendall Stubbs played bass.”

Jankel says that, during the month he spent recording Chazablanca in 1982, Compass Point was a chaotic but fascinating, place. “Steven Stanley was working overtime” he stresses. “I remember one time he’d been up all night, working on another project, so he comes into the studio and promptly falls asleep at the mixing board. So it wasn’t quite as efficient as I would have liked it. But when you work with genius, it doesn’t come in a regular shape.”

In this period, Compass Point was being pointed in diverse directions. For instance, Scottish post-punk funkers, Set The Tone, came down to cut material that inspired dance fanatics on both sides of the Atlantic (though Steven Stanley says the trio’s substance-fuelled rock-n-roll antics grew increasingly tiresome); the most bass-heavy number from the sessions, Dance Sucker, was given its ultimate shape through the mixing skills of noted New York club DJ, Francois Kevorkian, who travelled to Compass Point to mix an extended cut of the track. Kevorkian and Stanley also put their heads together to give a distinctive, otherworldly mix to an unconventional Spanish-language disco track called Obsession, voiced by a Cuban-born disc jockey named Guy Cuevas, who was then resident at a Parisian nightclub called Le Palace; the song had been constructed at Le Chien Jaune, the same studio in which Wally Badarou recorded the keyboard part of Pop Muzik, and after Kevorkian and Stanley were finished with the track, it sounded like some mutant disco number for outer-space aliens. Released in limited number by Island only in France, it has since become a highly prized collector’s item.

“It was the first time we worked together” says Kevorkian of Stanley, “and I just remember us ‘clicking’ right away—very smooth and professional.”

Some months later, noted photographer Lynn Goldsmith, who had often been present at Compass Point since being invited to the studio by the B-52s, voiced and mixed a very peculiar number of her own called Adventures In Success, which she describes as ‘self-help humour’. The track, which was mixed by Steven Stanley in 1982 and released as a 12-inch single by Island under her alter-ego alias, Will Powers, has a complicated genesis: summoned to Compass Point because Marianne Faithful, Joe Cocker and Robert Palmer were all working on material at the same time and Chris Blackwell hoped Goldsmith could photograph them together, Goldsmith wound up voicing a rhythm Palmer was building in the demo studio he had set up at home, after Faithful and Cocker failed to lay down vocals that Palmer found impressive.

Compass Point was being pointed in diverse directions. For instance, Scottish post-punk funkers, Set The Tone, came down to cut material that inspired dance fanatics on both sides of the Atlantic.

“The rhythm track was a steal from a James Brown thing” Goldsmith explains, “and after having enough drinks, Marianne starts singing some melody, but (Robert Palmer) said, ‘No, that’s not really it.’ Joe comes over and there’s more drinking going on; Joe sings a little bit and then he leaves, and (Palmer) said, ‘No, that’s not really it.’ It was about four o’clock in the morning and I had been thinking about if I were to make a record, what I would do; I thought that the human speaking voice was also an instrument and it could be used in certain ways, and I would pick tapes from preachers and use a vocoder on myself and come up with these kinds of positive thinking lyrics, because I thought that music had such a strong effect on our subconscious, that if we could have these lyrics in there and if I could be funny about it, then that would be different than what anybody else did. We have a guy here called Reverend Ike who has a big church up on Park Avenue, and I always thought that the power of those voices and the way in which they spoke was mesmerising, so I always collected tapes; Reverend Ike was my favourite, but I had lots of others.”

With such concepts in mind, Goldsmith asked Palmer to turn on his tape recorder. “By this time I was really pretty drunk, so I did my thing and he got so excited about it, he called up Blackwell, and Blackwell came over and got really excited and said, ‘I want to put this out.’ So I said, ‘No, I’ve been working on this for a long time and I have an idea of how I want to do it and I’m going to go off and do it my way, but Chris, if I come back with something that you like, I want an album, and I want you to be my producer.’ So he said, ‘OK,’ and that’s how Will Powers came to be. I left and I went to England, because I had to shoot something over there, and I asked Sting if he would work with me on the song, so Sting and I went into Island’s studio in London; he played all the instruments and I was on the Linn drum machine. Then I went down to Compass Point for my first session, and it was just Chris Blackwell, me and Steve Stanley in the studio.”

Goldsmith multi-tracked her voice in various guises to portray the song’s different characters, with the exception of a very deep voice that states the various ‘laws of success’, which was provided by a Compass Point stand-in. Although the rest of the album was later crafted with Steve Winwood and Nile Rodgers in New York and mixed by Todd Rundgren, the song ‘Adventures In Success’ was mixed at Compass Point by Steven Stanley, who added a minor keyboard part and made sure the single was complete with the shimmering dub version presented here. The video that accompanied Adventures In Success is also notable as the first to make use of 3D computer animation.

In addition to voicing Adventures In Success at Compass Point, Lynn Goldsmith was also present for the ill-fated sessions James Brown began at Compass Point in 1982. “Sly and Robbie were very excited about working with James Brown” she recalls, “but James really put people through the torture test. One of the great things at Compass Point was that there really weren’t a lot of egos, but James Brown was like a petulant child. I remember when I went to his house to photograph him, James is standing outside in pink rollers with Al Sharpton, and he says, ‘We gotta have you frisked, we gotta look through your bag,’ so I got frisked, even though I was with James Brown and Ali in Zaire in 1974.”

“James Brown had not encountered musicians like Sly and Robbie before. They would not accept any of his nonsense about having credit for songs he didn’t write. Plus, the sessions did not ‘happen.’ The music wasn’t great, and I gave the tapes back to James Brown.”

“The only one session that never work out, that ego cause the album to flop, was James Brown” laments Steven Stanley. “Chris Blackwell wanted Sly and Robbie producing James Brown, Alex Sadkin was the engineer and co-producer; it was a great idea. In Studio A, the session ready to begin: James Brown start to tell Sly what to play, so Sly, being humble and cool, he start to play it. So James Brown go to Robbie now, ‘Robbie, you play this…’ and when you check it, it was the same old-time thing, and I don’t think Blackwell wanted that. So Robbie gave James the bass and said, ‘You play that your blood-claat self.’ All the guys that he came there with worshipped him like a God, like, ‘Yes, Mr. Brown. No, Mr. Brown.’ And you know Robbie not going to like that, ‘cos he’s a human being like you and I, so you shouldn’t have to be doing, ‘Yes, sir, no, sir.’ He was this superstar, God-like thing, so it’s not gonna work—too much ego.”

“The near-clash happened between James and Robbie” recalls Wally Badarou, “but far from ending the project, it made it all the more exciting, because, for probably the first time in his long career, James had to let us take the leadership: ‘I understand you guys may have things you want to show me,’ James said, in a conciliatory attempt to save the momentum, the day after. ‘Yes, James, yes!’ shouted Sly and the rest of us. And soon after, we embarked into grooves of all kinds; we really had a ball, James included. I even came up with a It’s A Man’s World sound-alike song, on which James and I both played four hands on the piano, while his assistant was taking notes for lyrics to be written, based upon his vocal improvisations. By the end of the day, we had at least four tunes on tape, and things were looking quite good. Fred Wesley arrived on day three, congratulating us all for the grooves he’d heard on cassette, which nearly got Alex Sadkin fired for having made cassette copies—strictly forbidden by Mr. Brown. In a word, we had some treasured work in progress, at least treasured enough to get Mr. Brown back into one of his well celebrated habits: claiming 100% writing rights of all the work we initiated for him. As Chris wouldn’t let that happen, Brown simply quit, on the morning of day four. It was sad, but I don’t think it ever diminished the fundamental respect we all had for the Godfather of us all.”

“James Brown had not encountered musicians like Sly and Robbie before. They would not accept any of his nonsense about having credit for songs he didn’t write. Plus, the sessions did not ‘happen.’ The music wasn’t great, and I gave the tapes back to James Brown.”

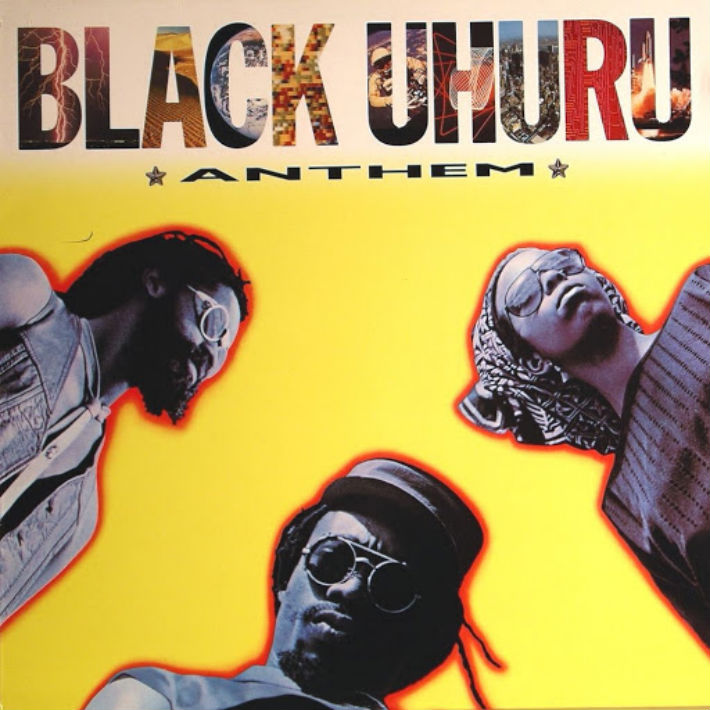

Lynn Goldsmith also photographed Black Uhuru at Compass Point in 1982 while they were putting the finishing touches on Chill Out, the album that really established their reputation in the USA. Like its predecessor, Red, Chill Out was largely recorded in Jamaica with Sly and Robbie at Channel One studio, its master tapes subsequently shipped to Compass Point for overdubbed embellishments and a final mix-down; another track to undergo a similar process the year before was River Niger, Sly Dunbar’s take on a moody number by West coast Latin funk pioneers, War, the title theme to a mid-1970s film about ghetto life. But even more noteworthy was the material Sly and Robbie subsequently put together with Gwen Guthrie, an African-American singer-songwriter based in New Jersey, who began her career backing Aretha Franklin in the mid-1970s.

“Gwen Guthrie’s our girl” says Robbie fondly. “When we did Peter Tosh’s Bush Doctor album, we asked for some background vocalists in New York; while I was balancing the vocals, listening individually, that voice struck me. I said, ‘Damn, who’s this girl?’ They say, ‘Gwen.’ Me and her became friends, and when we finished a tour one time, we asked her if she would come to Nassau where we were doing Bits and Pieces, ‘Don’t Stop The Music,’ which would be a Sly and Robbie kind of thing; Chris Blackwell heard our album and say, he think it should be a Gwen Guthrie album, and it started from there. We were doing dance music, seeing what a gwan in New York, fi get a hit.”

“I think during the Peter years, she get to like the music and our culture very much, and she had written a couple of songs…” adds Sly. “We had done a cover of the Yarbrough and Peoples song, Don’t Stop The Music, which came out as Bits and Pieces; we were just fooling around, but it did very good in America and that time we were on a tour with Black Uhuru and I say, ‘We probably should just do a project and get Gwen to sing on it’ and we called her up and she came down to Nassau and we cut the album. Chris heard we were down there doing some work and came to listen to the project and said we should sign her to Island records.”

“What a voice, what a singer, what a friend” adds Wally Badarou. “The sessions were just pure pleasure—slack as always, but pleasure regardless.”

The second album to emerge from the partnership, Portrait, contained a number of dance hits, of which the heartbroken Padlock is one of the most memorable. Tracks from the disc (and one from her debut) were later remixed for maximal dance floor appeal as the mini-LP Padlock by noted deejay Larry Levan of New York’s premier disco, the Paradise Garage, and it is Levan’s infectious remix of Padlock which is included here.

Meanwhile, in 1983, Black Uhuru finally recorded an album in its entirety at Compass Point, Anthem, which was ultimately awarded the first Reggae Grammy, but unfortunately signalled the group’s demise as protracted infighting resulted in the removal of lead singer Michael Rose. Then, in early 1984, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry turned up to record History, Mystery And Prophesy for Island, but his distracted frame of mind yielded uneven results.

Wally Badarou’s first solo album, Echoes, also surfaced in this era, as did the unexpected dance hit Land Of Hunger, by an oddball new wave-disco-funk aggregation called The Earons, whose band members referred to themselves only by numeric coordinates.

And only Chris had the vision to combine an American engineer with Jamaican drum and bass, with British rock guitar, with African-French keyboards. Every film director will admit it: when it comes to directing actors, the main thing is casting.

Although part of Sly and Robbie’s solo masterwork, Language Barrier, was recorded at the studio in 1985, along with Robert Palmer’s Riptide, and although visitors such as Judas Priest, Iron Maiden and Julian Lennon would subsequently record there, Steven Stanley says Land Of Hunger marked an unfortunate turning point for Compass Point. “After Land Of Hunger, I wasn’t getting any work” he explains. “Eric Thorngren was there in the latter part and I thought they were overworking him, day and night; I was there for two years and no work, so I call Blackwell in 1986 and tell him I have to go home.”

Perhaps because of his many different business interests, Chris Blackwell’s attentions were deflected away from the studio during the late 1980s, and a series of unfortunate circumstances led to a prolonged hiatus. First, the insidious presence of cocaine was becoming increasingly problematic in the region, with the corruptive crack derivative wreaking havoc on New Providence. Corrupt studio staff members who were hired after reliable employees succumbed to the drug are said to have begun fiddling the accounts to suit their own purposes, while some overseas employees turned to drink. After working on high-profile production projects elsewhere, Alex Sadkin returned to Nassau in 1987 to run Compass Point, only to be tragically killed in a car crash.

By the end of the decade, Compass Point had been virtually abandoned, leading Chris Blackwell to bring in engineer Terry Manning and his wife Sherrie, a video producer, to reactivate and administer the facility. Since reopening in 1993, it has again been home to countless international recording stars, particularly from the rock and hip-hop worlds, though to date, no attempt has been made to put together a house band as distinctive as the Compass Point All Stars.

Although Wally Badarou points out that Compass Point All Stars was never an actual band in the literal sense of that word, being instead a conglomerate recording entity of individual musicians put together and directed by Chris Blackwell, he is rightly proud of the extremely unique result of their creations. “I don’t believe anything could ever sum it up” says Badarou of the classic Compass Point sound… “like nothing could ever sum up the Motown or Stax sound. So much goes into the fabric of those sounds: the studio itself, the engineers, the producers, the artists, the vibes of the time, and only the specific combination of elements—even though very disparate sometimes—does the job. And only Chris had the vision to combine an American engineer with Jamaican drum and bass, with British rock guitar, with African-French keyboards. Every film director will admit it: when it comes to directing actors, the main thing is casting.”

Written by David Katz (author of People Funny Boy: The Genius of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and Solid Foundation: An Oral History of Reggae) and first spotted by RR on Robert Palmer’s site.

If you liked that then watch 50 Years of Island Records here and have a read of a short review of Darren Sylvester’s amazing Compass Point collection of photography here.