Glasgow based DJ and producer, JD Twitch chatted to UK dub master Adrian Sherwood at King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut on Monday 26th March 2012.

At King Tut’s on 26th March, Mark Stewart, one of the founding members of The Pop Group amongst many more noble and notable alternative music achievements and accolades, played a gig with his new band as part of what was a critically acclaimed UK tour. Keith McIvor AKA JD Twitch of Optimo (Espacio) was playing records in the support slot and Adrian Sherwood was the sound engineer. We introduced Adrian (who, in the 30th anniversary year of his crucial On U Sound label, has recently completed top notch remixes for Django Django and Peaking Lights as well as a new solo LP) and Keith for the following interview feature. Part two on Racket Racket in a fortnight. And, whilst you read, have a listen to this brand new Optimo podcast from Twitch which focuses on Adrian Sherwood’s dubwise productions.

For many people, often of a certain age with an interest in pushing the frontiers of sonic possibilities, Adrian Sherwood is unquestionably the greatest, most radical producer this country has ever produced. That may sound like hyperbole, but delve into the massive and varied body of work that has been given the Sherwood midas touch and ones ears will be seduced, assaulted, confused and caressed, often simultaneously. The term “mind blowing” could have been invented to describe his work and his great label, On U Sound.

In my late teens and twenties I bought everything that had his name on it without even listening to it first as I knew I’d love it (and I did). I am still tracking down the odd thing I missed all these years later and still wondering how on earth he got that sound or had the balls to make it so f*cked up. His work isn’t all about sonic onslaught and would often contain true beauty or combine both facets on the one record. A perfect example of that is the Ministry album Twitch which he produced that had such an impact on me that I stole its title for my DJ name.

I tend to think it is best not to meet one’s heroes in case the reality of meeting them shatters the illusion, so I was a little apprehensive of doing this interview. However, Mr. Sherwood was a true gent and a great raconteur and it’s possibly just as well that we only had limited time or I would have started geeking out and asking rather dry technical questions that would bore most readers into oblivion. While we only managed to touch the surface of all he has accomplished over the years it was a thoroughly enjoyable and illuminating 45 minutes spent in his company.

Keith McIvor (2012)

KM – How did you first hear Jamaican music?

AS – It’s funny because there’s a lot of chatter just now about Scotland getting independence. Well, at my school in England, I had loads of mates who were Scottish. Loads. People who’s parents were Scottish or one of their parents was. I had friends who were English but also Polish. Some Pakistani lads, some West Indian mates. That’s where the reggae came in, obviously. But, basically, it was all very mixed up racially – in a good way. England is everybody’s country you know. I think Scotland would get a lot more identity and freedom away from the bullshit of Westminster.

KM – For me it is just the same country. I’m against nationalism. I think we should have more powers up here, definitely, but so should every other part of the country. I just think it’s going the wrong way and it’s, kind of, stupid really.

AS – I wouldn’t mind blowing up Westminster and then we could have a lot more regional governments. But the point I was trying to make was that at school, where we were, people from Scotland, there were lots and lots of them. And lots of Irish kids and a few Welsh but you don’t really know or think about it because everything was so mixed. As I said, we had a lot of West Indians and my best mate from school, he’s dead know – bless his heart, was a guy called Gilbert. I used to sit in his sister’s room at the age of 11 and 12 and we’d be playing calypso, soul music and a few pop tunes that we all liked but lots and lots of reggae. And she would be playing things like Cherry Oh Baby and former winners of The Carnival in Jamaica mixed up with Lord Kitch or Mighty Sparrow. Lots of new reggae too like Winston Groovy and John Holt, Lorna Bennett… I got completely and utterly besotted with it. I also loved everything else; and the other kinds of music we were listening to but as the years passed other things came and went. There would be mind-blowingly amazing funk and soul tunes and some great pop tunes, like T Rex and Python Lee Jackson or Rod Stewart – they all had the odd good tune. I remember loads of stuff I liked that was non-reggae but as the years went on, the Jamaican stuff and to a point English reggae, was consistently getting madder and madder which appealed to me. The rude reggae, the political and revolutionary stuff… ‘Let’s bomb the church’ sort of stuff. It really got me. From the age of 11 I was hooked and it never left me.

I remember loads of stuff I liked that was non-reggae but as the years went on, the Jamaican stuff and to a point English reggae, was consistently getting madder and madder which appealed to me.

KM – How old were you when you were working for and running labels, Carib Gems and Hit Run?

AS – I used to go to a reggae club in the town where I lived called the Newlands Club or the Twilight Club. I think Dave Rodigan did his first ever gig there. I was DJing there when I was really young. The owner of the club, a Jamaican guy, was like my dad. He looked after me. My dad had died when I was very young and I had a step-dad but I wasn’t close to him so this guy took me under his wing and I started DJing in there when I was at school, on Saturday afternoons… Then eventually Sunday afternoons and then moved up to doing the early evening stints. I worked there with Emperor Rosco a couple of times and lots of other Radio 1 DJs and Judge Dread, who came down and did a PA in the club. I used to play early evenings before the sound systems. It had been a funk a soul club… Then in around 72 or 73 or something, it was a really, really hot summer and no-one was going to the club for months. The only people going were the reggae fans. It suddenly just turned into this reggae club whereas it had been a lot of soul drinkers prior to 72 or 73… So it went from a group of people who drank a lot and listened to soul to a group of reggae fans who would only want to drink one beer and smoke lots of weed. So it was only a matter of time before the club went bust. I was doing it from the age of 13 – 15, then the club went under. I had became good friends with the owner and his wife so when the club went under the owner, who had previously ran Pama Records, restarted the label and I got a little job doing promotions for them. Then we started our own distribution company out of the Pama office. That pre-dates Jet Star, Jet Star started after we had left. They basically copied the model we had created.

KM – Do you think any of the music on your early labels will ever get re-issued?

AS – There was a bootleg a couple of years ago of a Carol Kalphat record. That was a fucking character! I had to send a message asking not to bootleg any more of my tunes. The real problem with releasing that stuff is that if I start re-issuing it begins to bring people out of the woodwork which isn’t always worth it. I think it’s actually better that they are there and available as collector’s items and that’s it.

KM – You got into production at an incredibly young age as well. Can you tell us about that?

AS – Well the thing was I had started buying and selling the records and distributing them from our vans (at one stage we had four vans in the UK). So, I met loads of musicians and lots of people who I thought were musicians but it turned they actually were political gunmen, to be honest. They were hanging around with musicians and the people I was working with. Lots of people are actually very famous in that area and I thought they were musicians because they hung around with all the producers and musicians. It was a very unusual network of how people were protected and how they lived and socialised. I was quite innocent – only 17 at the time. I was selecting the tunes that we were putting out because I had the most enthusiasm for all the new music. That went belly-up after a while as well. Not Carib Gems but the distribution company. We were working on such small profit margins. A standard business today would be that maybe 30% of the dealer price would go to maintain the distribution company – but back then we were working on between 7.5 and 12.5% and, giving credit to the likes of HMV so a few bad debts later and we went belly-up… We done better with our own label and the ones we imported from Jamaica. When the distribution company went down I was left owing a serious amount of money – especially for someone of my age, 19. So that’s when I started Hit Run. I done Hit Run from the age of 19 to 21. Then that went belly-up too!

KM – So what was your introduction to the mixing desk and production?

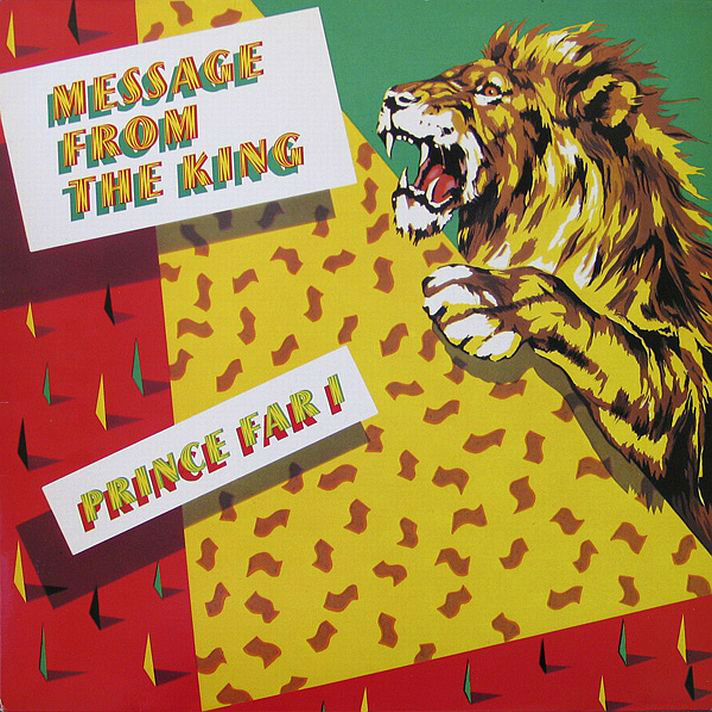

AS – Well, the first time I went in the studio I had met Prince Far I and I drove him down from Birmingham in this mad fog. That was when we wrote Foggy Road. And when we got back to London I introduced him to the other people at Carib Gems. This was probably around 1976. We done an album called Message From The King and pressed 500 white labels and then Virgin came in and licensed it. Far I didn’t quite have enough tapes to make up the album, so we needed a couple more. We went along to Gooseberry Studios where Dennis Bovell worked. We had Fish Clark on drums and Flabba Holt on bass (the original Arabs). We recorded Foggy Road and The Message. That was the first time I had been in the studio!

KM – How did you know what to do!?

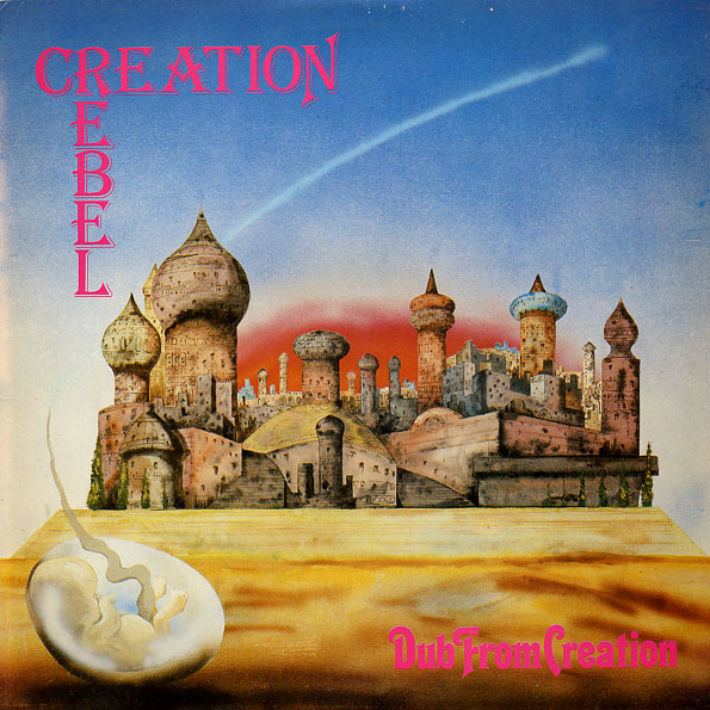

AS – I didn’t do anything! I was just in there, rolling spliffs telling them when I liked the music a lot and when I didn’t like it! I went in and just enjoyed the day. There were lots of arguments and fights going off but we made two really great tracks. Then, after that experience, I decided to make a dub album. And I hummed all the basslines, kind of off-key or in the key of A to the bass player – and then hired in a load of other musicians and made what you might call a ‘designer dub’ album, that was in 77. I called that Dub From Creation by Creation Rebel. I made the name of the band, even though it wasn’t really a band, Creation Rebel. That had been a name my mate Gerry wanted to use for a record label and I took it and used it for that release. So, we named the band Creation Rebel and hired a load of musicians. I still didn’t know what I was doing so I got Dennis Bovell to mix it for me. We done the whole thing in about four hours. I remember just wanting more and more reverb and Bovell would be saying “you’re mad, you’re mad” but he was actually really into the whole thing as well. We put it out and were selling it out the back of our car. I remember going to Greensleeves and they put the first track on and thought it was brilliant and asked for 25 copies. I was sat with Prince Far I one day in London listening to the radio and John Peel said, “Listen everyone I am going to play you the best dub album I’ve ever heard from this country” and then played three tracks back to back from the Creation Rebel album. He even left the gap going in between the tunes and didn’t speak for the whole three tracks.

My phone started going mad. Geoff Travis, who had previously said he didn’t like the record, now loved it. Rough Trade wanted 200 and all this sort of stuff. So I sold the first pressing of 1,000 and then done another 1,000. It only sold about 2 or 3,000 at the time but that gave me the confidence to record another album. I thought that rather than licensing tapes off Jamaican lunatics I’ll make my own tunes. Now, no disrespect to Jamaican lunatics because I love them all but I wanted to do my own productions. By the time it got to 1978 I cut an album called Starship Africa. I overdubbed it the following year and then released it in 1980. Rodigan said something like “What do you think you’re doing to reggae music?” when he heard it. I called him a Luddite in the Hammersmith Palais, I remember that. I’m still really pleased with the album. It’s mixed backwards. All the effects come before the beats, it’s unique. I wanted to do something madder than the last album. At the end of 1980 I had fallen out with the person I was working with. We are friends now, mind you, but yeah, in 1981 started up the current label, On U Sound.

KM – Which initially was licensed out to other labels?

AS – Initially I didn’t have any money so Geoff Travis helped with the first release. The second one I didn’t even produce. I was going to do it with different people. That was an album called Mothmen. That was ex-Durutti Column and some other people. The rhythm section of that band became Simply Red and then I ended up parking that one and also ended up having to give a lot of my stuff, that was never finished properly, away to Cherry Red. I gave them about 6 albums and a couple to Beggar’s Banquet, a couple to Statik… I was knocking out an album in about three or four days. I had no choice at the time.

KM – Studio time must have been more expensive back then as well. So you had to work as fast as you possibly could.

AS – Yes, it was. In those days you could buy a house in East London for £24,000 and a ten hour day in a studio would cost at least £300. So put that into perspective. People would be working for like £50 a week. Sales were rubbish too. We were only selling around 2 or 3,000 but yet we were selling out Dingwall’s in Camden two nights in a row and we could have filled out the Rainbow with Far I and some of the roots shows. The sales weren’t there because all the record shops and even the reggae shops would be selling things at the commercial end; and what we were doing wasn’t popular. It was far from being flavour of the month. We couldn’t compete with Island with the great Toots, the great Burning Spear and the great Lee Perry when we were making leftfield, really weird and obscure dub stuff like Prince Far I. We were selling in the region of 2,000, sometimes 4,000 records – but our gigs were packed out! Everywhere we done would be packed. The crowds weren’t really into buying records they were mush more into getting stoned and coming to our gigs and having a good time. We made a bit of money on the gigs.

In 1978 I cut an album called Starship Africa. I overdubbed it the following year and then released it in 1980. Rodigan said something like “What do you think you’re doing to reggae music?”when he heard it. I called him a Luddite in the Hammersmith Palais, I remember that.

KM – Back then people made tapes as well. So many people I knew had tapes of the African Head Charge albums for example.

AS – Yeah and that’s fair enough. What it did for us is made the gigs great. I remember having gigs and in the crowd you would have the Sex Pistols, The Slits, The Clash, Billy Idol… sometimes all these people at our gigs on the same night. The crowd would be watching the crowd! That’s how I met Ari Up – we did the Slits tour with Don Cherry and Happy House. We were guests with Prince Hammer, then the next month we would support The Clash. We had a bit of a ground swell. We knew The Ruts through Misty and Roots. With a lot of this I was in the right place at the right time and a complete fan.

KM – For me looking back at the punk years the most interesting records were the ones where a bit of dub crept into the sound. Like New Age Steppers and things like that.

AS – It’s funny. It was totally coincidental. I first met Mark (Stewart) in 1975 when he was a schoolboy. I was a couple of years older but knew him and then a few years later he had the same management as The Slits so I hung out with him and and Ari and everybody.

KM – Moving forward a little, there was a period in the 80s when you did a phenomenal number of remixes. How did you go about doing a remix?

AS – I was taking the same approach as I would have done with dub and disassembling stuff. I’d have an AMS which had samples in it. So I could take snares out and replace them and then completely distort bits of it. Mess around with fades and delays. Copy it onto a multitrack and mangle it all up and send it back. And earned as much money as I could get doing that.

KM – Back then remix fees were better as well?

AS – People always think On U must have done really well but it didn’t really. I must have put 100s of 1,000s of pounds into the label because I kept thinking I was going to have a really big selling record and I think the best ever seller was maybe 40,000 on the label. So I kept ploughing away doing jobs to prop up the company. All through my life when I was doing well, I was just drawing a wage from On U. That was all I ever did.

KM – How big an organisation was On U in terms of employment?

AS – At it’s height we had nine people. That’s when we had two studios, a warehouse and an office. At that point I was losing about £1,000 per week and taking loads of drugs and falling to pieces basically. It wasn’t a good time.

KM – You also did a lot of production for bands. There are very few records I will buy now because of who produced it. That era seems to have passed. There are still great producers but I’m unlikely to buy a record simply because of the producer. There are a lot of bands I got into because of who produced them. Pankow are a band I got really into but only bought their stuff because you had produced it for instance. Did you enjoy that era when your input was so important to the sound of the acts?

AS – I always tried to get my own sound. I always remember Prince Far I going on about “my sound” – He prided himself on having the lowest one-drop in the world, you know, and the most space and super-heavy bass and bellowing vocals. And you could actually identify his productions; and if you listen to the great producers, not just in reggae, they have always had their own sound. I worked very hard to establish one myself. I was always very conscious of this because I knew it would put me in good stead. I was for a long time only really comfortable working in the reggae area then I met the funk lads, Tackhead and we got on really well so that drew me into that. Mark had pioneered a lot of the industrial stuff so that lead to working with Nine Inch Nails. Nine Inch Nails, now they used to follow us around to all our gigs and I was forced to do the first tune with them by Keith Le Blanc. I didn’t want to do it. We got £500 and it sold a million fucking records. That was a bit annoying. They came back and asked us to do more stuff but I was too busy doing other things you know.

Read part two of this interview feature here. And, as ever, you can find more reggae and dub related music at our Reggae For Bed section.

Pingback: Dub From The Pub: How Adrian Sherwood Made UK Music Amazing | FTP Soundsystem

Pingback: JD Twitch Meets Adrian Sherwood (Part 2)

Pingback: Mais podcasts: Radio Belbury & JD Twitch | 33 – 45

Pingback: Stuart Leath Interview

Pingback: Optimo Podcast 12 | Adrian Sherwood On U Sound mix part 2 (dub) & part 1 - dub.com