Neil Macdonald from Bite My Wire chatted to Karl Bartos earlier this year. A must read for fans of Karl’s and, indeed, for fans of Kraftwerk – the band with whom he made his name. A great read.

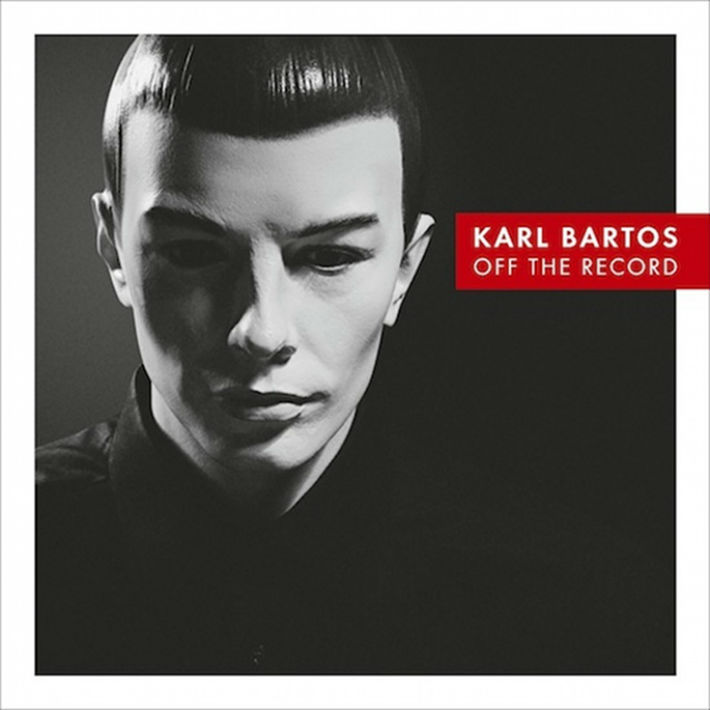

Karl Bartos was a member of Kraftwerk during their most iconic, productive era. As the band’s classically-trained percussionist an co-writer, he had a massive influence on the sound and direction of Kraftwerk, and ultimately – through records like Trans-Europe Express, Man Machine and Computer World – on the advancement of electronic music and how we know it today. Since leaving the group in 1990 because of the continuing slow creative process brought on by the band’s perfectionist approach, Bartos went on to release a number of solo albums, work with Johnny Marr and Bernard Sumner in their band Electronic, produce music for others and even release the Mini-Composer iPhone app – which is a lot of fun. His latest album, Off The Record, draws from material he has gathered from the last 35 years of his life and is out now on Bureau B.

So I understand that this new album is made up of pieces of a ‘musical scrapbook’ you’ve been building up over the years. If that’s the case, does the record reflect more on where you are, musically, now or at the time you had the idea?

Hopefully the result is the best of both worlds! When my label approached me, they said “Hey Karl, haven’t you got any old tapes in the attic?” I refused, but they kept asking me and asking me, and they just wanted to put these old tapes from the attic out. Finally I got convinced by the idea, and I transferred all my old tapes from my archive into the computer. When I saw all the dates, 1977, 1978, and so on, it looked like a kind of ‘acoustic diary’. It wasn’t meant to be an acoustic diary but it became an acoustic diary by seeing all the data. Once I transferred it into the computer it was easy for me to just put bits together, and I did what we call recontextualisation. It’s easy to recontextualise material on the computer! I took these bits, these jottings, from here and from there, and they were not real compositions, but just jottings. Some of these scribbles I took into a place called Kling Klang studios, and they became rather famous. Some of them, I didn’t. Some of them I took there and they seemed to be a misfit, or they just didn’t belong to the current record. Unfortunately, we made so few records at the time, in the 70s and 80s! So I ended up with this encounter. Karl Bartos that I am now, with this youngster, this whippersnapper from the 70s and the 80s. So I could combine this naivety which a 20-something guy has, with my experience now, which led to this record that is in our hands today.

Was it easy to recontextualise the old stuff with modern technology? Bearing in mind you weren’t writing all that stuff with modern technology.

Exactly. This is as developed as we can be, having a computer to splice these things together. In the early days you couldn’t make an archive, and technology wasn’t as accessible as it is nowadays, so it was a great help. It’s a complete mash up actually, of the technologies from the 70s and 80s, and nowadays technology. So again, the best of both worlds. This record couldn’t have been done in the 70s or 80s.

When you were in Kraftwerk, you were having to develop the technology to make music yourselves. Now anybody can make music on their computer. Do you think technology has affected people’s creativity?

Yes, of course. The medium is always responsible for the content. It won’t affect me, because I did my piano lessons when I was young, I played in an orchestra and I played guitar. So I use technology as a tool. But certainly, if you take your first steps in making music when you open up a computer and load some music software, then of course it will affect the content you are producing. There’s no way around that. But I am just listening to music in my head before I compose it, and I’m not depending on software or anything else.

Kraftwerk already existed when you joined. Were you invited in as a writer, or were you initially just asked to join as a musician?

It was 1975 when Florian called my professor, and he was just asking for a classically trained drummer. So I got the job as a studio musician when I started, then I ended up on this famous US tour in 1975. It was a really good chance for me to make myself acquainted with the American music culture, and it really changed my life. That was the Autobahn tour, then I played the drums on Radioactivity and Trans-Europe Express. I already had some input then but unfortunately my name is not on the records. By the time we did Man Machine I got invited to be an official co-composer, and I found it very natural. I had already been round for two records, and had my input on them, and finally I got the credit on Man Machine. So it was a natural process.

What electronic music do you enjoy personally?

Stockhausen. Pierre Schaeffer from Paris, he invented what we know now as Musique Concrète. Pierre Henry… I must confess I don’t listen to new music any more, or on the internet. It’s just so confusing.

It was 1975 when Florian called my professor, and he was just asking for a classically trained drummer. So I got the job, then I ended up on this famous US tour in 1975. It was a really good chance for me to make myself acquainted with the American music culture, and it really changed my life.

Do you think that because music is so easy to make and release now, that there’s too much of it?

There can’t be too much music in this world. We badly need music, and we badly need people to play music. This is very important for our soul. Music comforts us. It’s really good for every one of us to sit down and play guitar or play a laptop, or sing in the shower. Every one of us needs music. I found out I can only relate to music which comes from people I know personally. Somehow you have to make a distinction, because there’s only 24 hours in a day and I can’t listen to all of it.

Do you think it’s because you know where these people are coming from already? Do you think that if you listened to music made by somebody you didn’t know personally that you wouldn’t know the point they were making, musically?

It was much easier when I was young. We had (pirate station) Radio Luxembourg, and there was just the charts, and in the 60s and 70s you were sure that the first ten numbers were quite good. Although once in a while there was Englebert Humperdinck playing at number one. But normally, in the 60s, you would find people like Jimi Hendrix at number one, or the Beatles, or the Kinks. It was really good music and the message in the music was fantastic, and in some ways it changed politics and it changed society. If you look into the internet, this music is still around! It doesn’t disappear. There’s music that was created in the 90s that has disappeared. You can’t find it any more. So it was much easier in the early days of pop music. I don’t want to know about the latest Lady Gaga record anymore, it’s not worth it. It’s worth it if one of my students, or a friend, sends me music. We can have a conversation about it, and I don’t get confused by two million songs on the internet. It’s too much.

What’s your average day?

I get up and I go out. I live on the outskirts of Hamburg, very close to the river. So I go to the river and exercise for an hour and a half. I go with the dog. Hamburg, as you know, has a big harbour so if I’m lucky I might see the Queen Mary II coming in. I’m not lucky all the time. By midday I’m ready to go to the studio. I need the contemplation and routine to regain motivation.

Do you listen to your own music?

No, you can’t. You need distance. I can’t listen to my new record because I’m close to burn out now.

Is that because it’s a solo record? Would it be different if it was a record you’d made with other people?

Even when I worked with Johnny (Marr) and Bernard (Sumner), you put all your life into the record, and then it’s finished. I’ll tell you another secret. When you start a record, whether it’s a solo record or it’s a group attempt, the first thing you want to do is to change the world. But when you’re finishing it, you just hope you’re getting away with it.

How did you come to work with Johnny and Bernard?

Bernard listened to my first solo record, and must have though “Oh, this guy’s solo, maybe we can get him to do some electronic percussion on our tracks”. We ended up co-composing a lot of the music so I ended up writing a lot of songs with Bernard and Johnny. We’re still friends, it’s amazing.

You mentioned earlier The Beatles, The Kinks and Jimi Hendrix. If that was what you were listening to when you were studying classical music, what made you want to play electronic music?

After my initialisation with music, I learned all the famous songs from the 60s era. You had to. They were so beautiful, and it was like magnetism. I learned how to play guitar, and I learned pop music, and finally I understood pop music really well, by analysing it and playing it. Copycat style, in cover bands. It’s always the same approach. You copy it, then you compose songs ‘in the manner of’… If you’re really good, you find your own identity and you come up with something new…

Keith Richards used to say. “It’s funny, if I play an old blues song, it’s funny to see how it turns into a Keith Richards song”. That’s the whole story of creativity. I was quite young, but I wanted this to be the thread of my life, I wanted to become a musician. Coming from a German background, I thought I had to study it at university. So I went there, and after I discovered Chuck Berry I discovered Bach and Beethoven and I ended up becoming a percussion player. By studying percussion in the 60s and 70s you make yourself acquainted with Stockhausen and John Cage, and you learn about serial music, minimalistic music and electronic music. So I thought “OK, here is the guy who influenced Sgt. Pepper, this is Karlheinz Stockhausen, he lives very close to us!” Dusseldorf and Cologne are very close. And then I ended up in Kraftwerk, where I got it all together. We had the pop music approach, and we had the German electronics, all at once.

With all your musical training, and your interests, did you find it easy to make an album like Man Machine?

(Long pause) Yes. Normally, if you’re following the lectures of Karlheinz Stockhausen, you would exclude pop music. But this was my first step, my initialisation, so it was very easy to have those different ingredients and bring them all together, and on top of that to add some funky rhythms by James Brown. If you mix them all up in a perfect cultural mash up, and I had this feeling we were going to generate something quite authentic.

You didn’t really have anybody to base your music on, and that’s never going to happen to somebody again.

We had to be authentic. I like I Am The Walrus, but it’s not me. It belongs to another heritage. I can admire it, and I can praise it, but I can never be it.

What are your plans for the rest of the year?

We have a screening in London, at the Rough Trade record shop, and I’m doing a lot of promotion all over Europe and America. Then I’m going to prepare my live show, which is an audio-visual show. I’m really into the convergence of image and sound.

What do you think of Ralf touring as Kraftwerk?

My lips are sealed. If Sir Paul McCartney plays, it’s a Sir Paul McCartney concert. It’s really great how he does that.

Yeah. He doesn’t call himself ‘The Beatles’. Anything else before we finish up?

I wish I had learned to jump on this little machine, the skateboard. I wish I could, but I am just not able to. I would break a leg. I’m not good at balancing!

This article first appeared on Neil Macdonald’s Bite My Wire, which is well worth keeping an eye on.