Neil Macdonald from Sidewalk Magazine and the Bite My Wire blog chatted to a band who, for us, are one of a handful of truly exciting new groups to emerge in 2012, Django Django.

With their outstanding debut album appearing seemingly from nowhere earlier this year (only two super-low key singles preceded it) Django Django have recently embarked on a tour of much bigger venues than any ‘new’ band might expect to – and it seems that translating their avant psyche/indie/kosmiche/drone/techno pop from its beginnings in drummer Dave’s bedroom to 1,000 capacity venues hasn’t been a problem, because they’re absolutely killing it live right now. Dave and singer/guitarist Vinny gave us their time.

The tracks WOR and Storm have been around for ages – they were both singles a while ago and have been up on YouTube for a couple of years. What have you been doing in the meantime?

D: Loads of stuff. I had to finish the post-grad I was doing at Chelsea Art College, Vinny was busy being an architect… Trying to make money. The weird thing was, we put out Storm and Love’s Dart on this little Glasgow label called Shadazz in 2009, and we had no more music. We didn’t have a band, or anything.

Those were your only songs?

D: We maybe had three or four, but they were so rough, and we just weren’t ready. After we did that we were just like, “Shit, what do we do now?” We did WOR to sort of bridge the gap while we were learning to be a band.

You make it sound like it isn’t a significant part of the album!

D: No, no, no! It’s still my favourite track, and it’s one that people love live. But we had to literally hide away, and make an album, become a band and get a record label. Then when we did finish it we had to get it mixed, and that took ages.

V: Yeah, and then there’s the whole marketing thing, like when it should be released, and it was released eight months after we delivered it. But we did most of it at Dave’s flat. We didn’t want it to sound lo-fi, so there was a lot of learning to be done. We were trying to get good production values in terms of the equipment we had, which was next to nothing. It took so much longer than when you go into a production suite, and there’s mics here, here and here, when the guy just mics it up and you’re ready to go. It was kind of the opposite of how you’d have done it in the eighties or nineties where you’d build up loads of songs and play loads of crappy bars and just gig for years and get really tight; then an A&R guy spots you and you’re ready to go. It was the opposite for us. We were trying to catch up with ourselves.

It was good to have a label that let us do it the way we wanted to, and do it in the flat rather than put us in with some super-producer or something.

So did you have a supreme amount of faith in the album, to know that you could go away and make it yourself, and then just appear with it?

D: No, I think it was more that we just took one step at a time.

V: We kind of just went along with the knowledge that there wasn’t much heat on us. That’s what it felt like anyway. It gave us the space to keep going with it. Obviously when we did Storm it created a bit of a buzz, and that kind of spurred us on to do more. Each new thing kind of geared you up for the next stage. It took us about a year to get the live set-up going, to be able to interpret the songs, because there’s a lot of layers and they’re quite complex. How do we represent that on a stage, with four people, when potentially you’ve got 150 layers on a track, you know? To pick the key things, then make that work was the hard part.

D: We’re probably quite stubborn. We thought “Well, if we like it, then that’s all that matters”. With every track, we just thought “Does it reach our standard?” And then we had an album we liked, and we thought that was a good enough start. It was good to have a label that let us do it the way we wanted to, and do it in the flat rather than put us in with some super-producer or something.

V: They came in at the right time, because we had the album almost done.

Who produced it?

V: Dave.

D: Yeah, I produced it, and then we mixed it in a proper studio with a huge outboard mixing desk and echo rooms and stuff like that. That just brought it up another level.

Was it a big move going from making an album in Dave’s flat to playing in front of thousands of people, with nothing in between?

V: I think our heads were so stuck in it we almost lost sight of what was happening. It’s like if you’re writing a novel, your friends eventually stop asking you how the book’s going, and it gets quite claustrophobic.

I remember first getting Boo Williams stuff on Relief and thinking “This is house, but it’s nuts”. It wasn’t like anything I’d heard, and I get that when I hear some of that Night Slugs stuff.

You get lost in it?

V: I think so, yeah. And you’ve heard it so many times, because you’re always tweaking things in the recordings. You might have heard a track 1,500 times, and you can’t make a critical judgement on it anymore. Obviously it’s been really great how it’s been received, but we’d have been happy with a lower level, like a ‘cult buzz’. Our aspirations were quite low.

D: Yeah, it’s kind of smashed my expectations. I mean I hoped that people would like it, because we spent so long on it, and we really put everything into it. We just hoped that people would ‘get it’. I didn’t think it would break out like this, and be played on the radio, and us do gigs this big… I thought that maybe that would come some day, after three albums, but I never thought it’d be today. It’s great. I guess we feel that we’ve just slowly built up and built up, so I feel that we’re kind of ready for it now. I think that if we’d done the album earlier and then been thrust into this situation we’d be “Oh, shit!” But it’s nice, everything’s come at the right time for us. It’s been good.

Is it your day jobs now?

V: Yeah.

D: Yeah. For this year anyway. Which is good, because it was a nightmare to try to work around jobs. This whole year is dedicated to touring, and we’re going to Australia, America and Japan. You can’t expect to keep your job!

Have recent changes in technology – with the downfall of MySpace and stuff like Spotify getting massive during the time that you’ve existed as a band – changed the way you approach making music or approach marketing?

D: I think MySpace totally revolutionised the music industry, and it became clear to us that when you put four tracks up on MySpace, you’ve released an EP. Whether you like it or not. People will take those recordings and copy them, burn them, share then and put them on CDs. We soon found out that that’s it – you’ve released music to the world – and I think that’s great. It made everything really fresh for bands. It was exciting.

V: It was great that it by-passed all the formal routes people take to make music.

D: And it took ten minutes. You didn’t have to wait for anything. You could put a song up in the morning and then by the evening you had a load of comments and feedback. People have got to move with technology. I’m a stubborn vinyl-head – I never moved to CD, and MP3s are beyond me a bit – but I don’t think it matters how you consume music. It’s a personal thing.

But does it affect how you make music? Were you writing for a ‘Side A’ and a ‘Side B’?

D: Not necessarily two sides, but definitely ‘an album’, rather than just tracks to be put up here and there. But that’s probably from growing up, from listening to The Beatles, and Neil Young, and Pink Floyd – proper albums. We wanted to do it like that, even subconsciously. As I say, I only buy vinyl, but you can’t tell 15 year-old kids to go and get a record player or they’ll think you’re mad. To be honest I think most music consumption now is done through YouTube. I do that myself too. If I’m going for a shower I’ll put on an album, or a mixtape on YouTube.

It was the first opportunity for a lot of people to hear your music.

D: Yeah. I think for as much music as we’re into, whether it’s dance or hip-hop or whatever, I guess we are in an ‘indie’ bracket, and you’re not going to go down to (legendary London dance music retailer) Black Market Records and ask for a dubplate of us. You’ve got to be out there on blogs. I think blogs and SoundCloud are the record shops now, I think that’s where people get fresh stuff. I won’t DJ music unless I’ve got it on vinyl, and it’s becoming more and more difficult because stuff doesn’t appear on vinyl so much.

So it was an easy decision to have the album released on vinyl?

D: Yeah. We would never have signed to a label that weren’t into doing vinyl.

What was your musical upbringing? What bands brought your individual outlooks together?

D: I guess we were all into sixties psychedelic stuff, from our parents record collections. Pink Floyd, The Beatles, Love, Bob Dylan… When I was eight or nine I was digging around in those, just discovering the classics really.

That isn’t really stuff that’s reflected in the music you do now though.

D: I think it’s there, deep in it somewhere.

V: I think that’s the foundation, maybe, that you build everything else on. I suppose like most people with a healthy musical outlook we were open to new stuff. Like you meet guys who are 50, and they were into punk, but now they listen to some post-dubstep stuff or something. It’s great when you meet people like that, who aren’t stuck in ‘their’ era.

So what new stuff are you digging then?

D: For me, Night Slugs stuff. Jam City. This new breed of house, Pearson Sound. It’s this mish-mash of dubstep and UK garage, mixed with classic house. I mean, my first love was hip hop. I discovered Public Enemy and spent my youth DJing hip-hop, and then jungle. I think that after the jungle scene I started getting into anything and everything, and just started buying loads of reggae and calypso. I think the two things that have stayed with me throughout my record collection are hip hop and house. Chicago house, like Relief Records and Dance Mania.

I’m a stubborn vinyl-head – I never moved to CD, and MP3s are beyond me a bit – but I don’t think it matters how you consume music. It’s a personal thing…

I think that’s reflected in your production.

D: Well that’s what I was doing before I met Vinny. I was sending tapes away to Trax records. I’ve always had this obsession with certain sounds of Chicago house, and I think now that kids are discovering that music again. In Jam City you can hear stuff like Wax Master Maurice or Boo Williams, those guys who were making – at the time – this mad, new, out-there music, and I remember first getting Boo Williams stuff on Relief and thinking “This is house, but it’s nuts”. It wasn’t like anything I’d heard, and I get that when I hear some of that Night Slugs stuff. It’s almost avant garde, and it shouldn’t work. That excites me. Clone Records as well, from Rotterdam – the Jack For Daze stuff is really good.

In the way that you got to this warped version of house through Chicago house – do you think that people buying your record will get switched on to weirder stuff?

D: Maybe. We post up a lot of weird music that people might not expect that we’re into. People might be baffled and hate it, but I think it’s what keeps us us, you know? I mean, I was making house, Vinny was writing songs and we fused those together. On Waveforms, the rhythm for that was for a dancehall record that Daddy Freddy was on that I did in Edinburgh years ago, and I just took the beat and it became Waveforms. It’s like the psychedelic indie pop, then you’ve got this bashment thing, and it works. So there’s bits that have just fed in, but I wouldn’t want it to sound like a guy who makes house meeting a guy who writes songs. It’s got to sound like Aphrodite’s Child, where you’ve got Demis Roussos, and you’ve got psychedelic rock. It’s got to merge and become one sound. And sort of transcend genres, because I think the best rock, or pop, or indie breaks out of being just that. That was something that I always hoped we’d be able to do.

You’re kind of in the deep end now, basically starting out playing to big audiences. What live music have you seen in your lives that’s inspired you?

D: Well, my brother was in the Beta Band, so watching them was always a bit “Fucking hell!” You could hear stuff like Public Enemy in their music. I think that that’s what keeps us at a parallel with them. We get compared to them a lot because we’re not just into one thing. Watching videos of Public Enemy and De La Soul was a big thing when I was a kid. I had this skate video called Attack, and it was one of the first skate videos I remember seeing, and it had this fantastic, breakbeat, bombastic soundtrack.

Bomb The Bass.

D: It was Bomb The Bass. I don’t know if you know a skateboarder called Gordon Dear, a Fife guy? Goosho? I grew up skating with him, in the Factory in Dundee, and we got hold of this Attack video. I asked Gordon what the soundtrack was, and he said “I’m pretty sure it’s Public Enemy”, so I went with my mum to Our Price and I got Fear of a Black Planet album on tape, and got it home, and it wasn’t the music from the video. Because that was Bomb The Bass, but I was just hooked then, completely drawn in. I’d only ever heard The Beatles, and my parents’ record collection, until then. It was like “Fucking hell! This is NOW!” It was bands like that who got me excited about wanting to make music.

V: It was probably the Beastie Boys for me. I saw them about five or six times. I saw them at Lollapalooza in Chicago when I was 15 – I’d never been out of Derry before – and it was in this massive arena. That summer, they’d just done Ill Communication, and it was all over MTV. I was watching MTV a lot out there, because we didn’t have it at home, and then to see them was totally mind-blowing. Where I was from, there was no hip-hop around, so it opened this new channel. I went to see them every time I could after that.

I think when we try and make music it’s like a beast that takes on its own form and it feels like we’ve created a monster half the time. I think our only philosophy is that we just go with it, and let it happen.

Have you had time to think about what you’re going to do next? New album?

D: New album. Trying to think about how we’re going to approach the sound of it. I think this album was like a lifetime of musical influence, just sort of puked out.

V: Very slowly.

D: Yeah, puked out very slowly! Dribbled out over three years.

So you’d describe your album as ‘dribbled puke’?

D: Haha! Yeah. The next one’s going to be projectile vomit!

You’re obliged now to have a ‘difficult second album’ anyway…

V: It’s good in a way, because I don’t think we’re cornered. Sometimes that can happen if a band have a very particular sound, and you think how they’ll go from there. Our album kind of leaves the door open for us to do whatever.

D: As much as we ever try to think about it, I know we’ll sit down to make it, and it’ll come out totally in its own. I think when we try and make music it’s like a beast that takes on its own form and it feels like we’ve created a monster half the time. I think our only philosophy is that we just go with it, and let it happen.

V: Go with the accidents. Loads of the things we’ve done on this were kind of flukes, or accidents. Like you’ll put the drum machine on, and it’s at the wrong speed for the song, and you play with it anyway, and it goes somewhere else…

So you can’t really approach it the way you did the first one?

D: I think that would take too long now. I don’t hink we’ll have that time. We’ve got our live heads on now anyway, trying to be a live band that people can come and see, and hopefully think it lived up to something.

Why are you called Django Django? I heard it’s got nothing to do with the jazz guitarist?

D: Yeah. We wanted something like Liquid Liquid or Duran Duran… More Liquid Liquid! We were looking around the room, literally going through doubles of everything in the room, and there was a rave record called Son of Django – I guess named after the Western, although I never knew that – and it just became Django Django. It was just me and Vinny sitting with a MySpace account, and we’d never have thought we’d be sitting having made an album, talking to you now, waiting to play ABC1 with the name Django Django! We were probably pissed, after work. I asked Andy from the Phantom Band what he thought, and he said it was the worst name he’d ever heard. That was good enough for us. Although I think they were called Tower of Girls at the time, which is a great name.

It’s a better name than the Phantom Band. Anyway, thanks for not spelling your name with triangles instead of ‘A’s.

V: Haha!

D: Haha! Yeah. A ‘D’ and a ‘J’ is hard enough. DJ Ango DJ Ango…

This interview first appeared on interviewer Neil’s Bite My Wire blog. Neil also writes for Sidewalk Magazine.

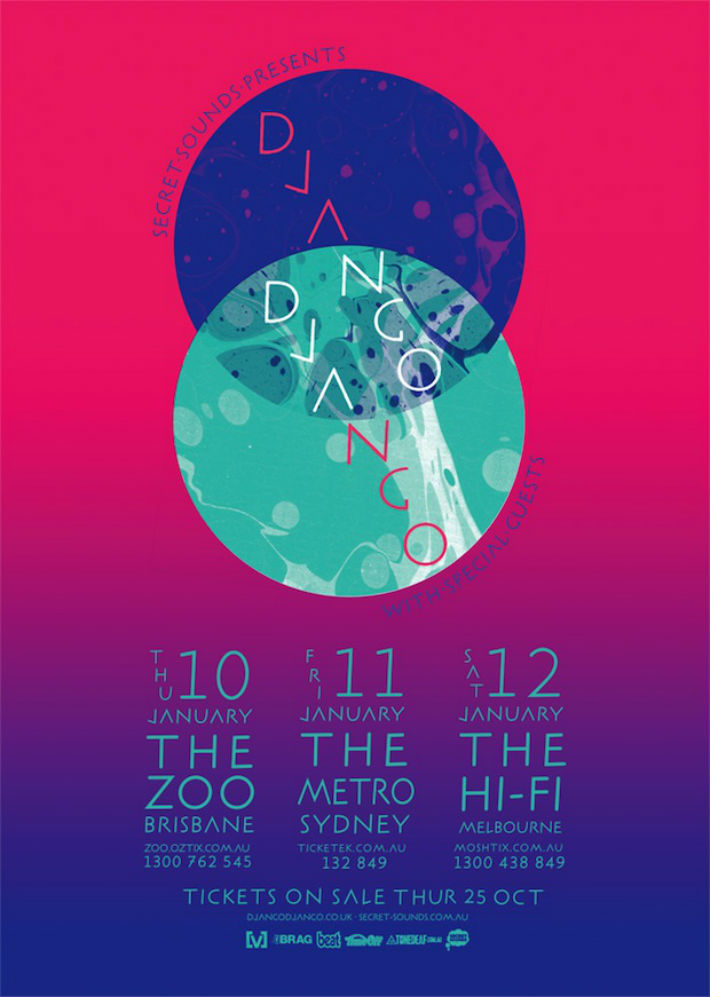

You can buy Django Django records on their official website. And the amazing pink and purple poster in the middle of the article is for the band’s forthcoming mini-tour of Australia in 2013, for our friends down under.