First class Scottish author and all round top chap, Alan Bissett takes a look back at the rise and fall of the Britpop Empire.

So is the fad for the Eighties over yet? For ages there it was all assymetric hair, drainpipe jeans and everyone raving about how great Total Eclipse of the Heart sounded.

Yes, the razzmatazz of the decade that taste forgot, but miners didn’t, was very much back for a while. The logic of retro is such that each decade nostalgically looks back at least two before. Dylan reached for Woody Guthrie, Lennon for the sounds of English variety and music-hall. Seventies film and TV swooned for the Fifties, all Grease, American Graffiti and Happy Days, while The Clash – who declared “No Beatles and Stones in ‘76” – went ‘Jimmy Jazz’ and ‘Brand New Cadillac’ on us. The Eighties stalled on the Fifties and early Sixties, a la Dirty Dancing and endless adverts soundtracked by rockabilly or Memphis soul. The Nineties, thanks to Mr Cobain, recalled punk, while hip-hop sampled everything it could lay its hands on. Then came the veritable smorgasbord of cultural nostalgia that was Britpop.

That is the sound of pop eating itself, as we enter into the second coming of the Nineties, itself the most retro of all decades. Blur, Suede and Pulp enjoyed massive comebacks recently, and the excitement surrounding The Stone Roses reunion looks set to eclipse them.

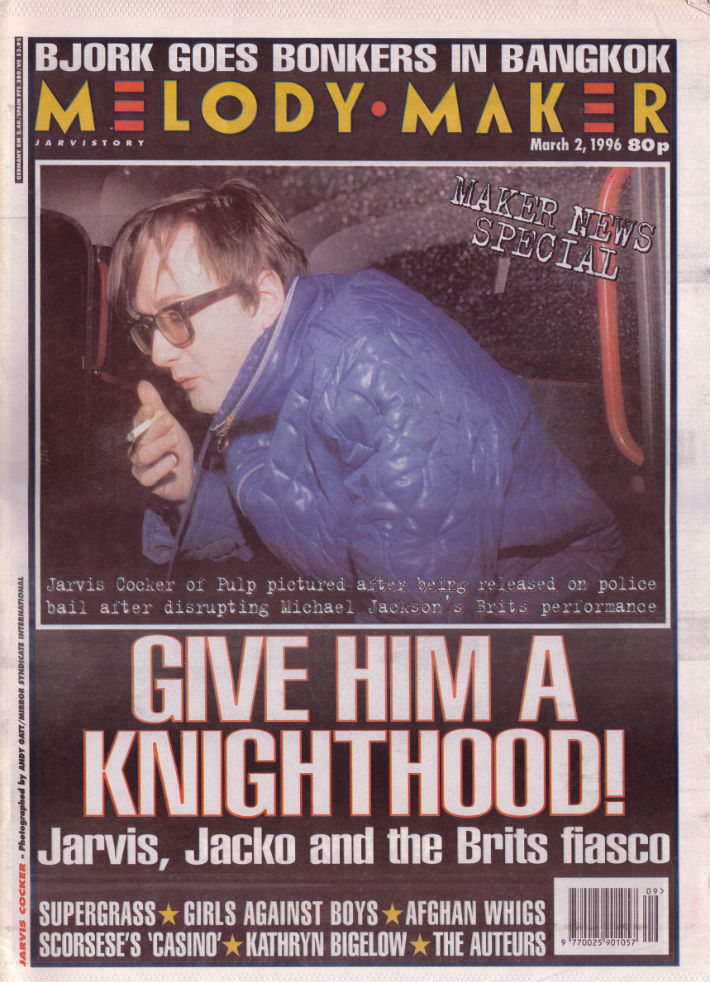

That is the sound of pop eating itself, as we enter into the second coming of the Nineties, itself the most retro of all decades. Blur, Suede and Pulp enjoyed massive comebacks recently, and the excitement surrounding The Stone Roses reunion looks set to eclipse them. Primal Scream toured Screamadelica in 2011, the same year that Jarvis Cocker was voted second coolest person in the world by the NME. Blur are to be awarded a Lifetime Achievement at the next Brit Awards.

Noel Gallagher has reinvented himself as a successful solo artist. Britpop might be remembered chiefly for its pantomime elements: the Blur v Oasis pissing war or Jarvis dethroning Michael Jackson at the Brits. So now – especially given the fragility of this Union of Great Britain – is a good time to go back and examine the complex and contradictory signifiers that made up Britpop.

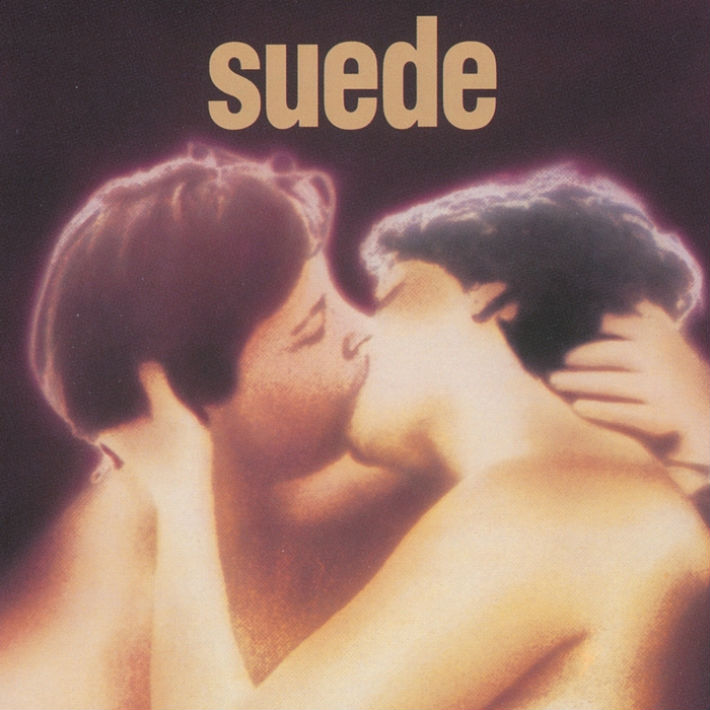

It was, more than any other genre of rock music before or since, a magpie arrangement. Almost everything from the past was fair game for Britpop’s rapacious appetite. The Beatles, Bowie, The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, The Who, The Sex Pistols, The Jam, Led Zeppelin, The Small Faces, The Monkees, The Smiths, T-Rex, Slade, The Stranglers, Wire, Syd Barrett, all were regurgitated to various degrees and with, it has to be said, considerable elan by Britpop’s prime movers, that is Suede, Blur, Oasis, Pulp, Elastica and (on certain albums, at least) The Stone Roses, Primal Scream and The Manics. Britpop spoke, initially, the language of youth and revolution, but the most stringent questions it asked of previous generations were: Are you British? Are you white? Okay, you’re in. Herein lies the key to Britpop’s underlying conservatism. But more of that later.

Short history lesson. Britpop emerged, it is generally agreed, out of a lull for UK indie, as Nirvana gripped the alternative imagination and processed pop filled the mainstream. The emergence of Suede’s self-titled debut in March 1993, then Blur’s Modern Life is Rubbish and Paul Weller’s Wild Wood a few months later, signalled a sea-change. 1994 saw the genre’s decisive arrival, with Blur’s Parklife, Oasis’s Definitely Maybe, Pulp’s His and Hers, The Stone Roses’ Second Coming, Primal Scream’s Give Out But Don’t Give Up and Elastica’s eponymous first album. All of a sudden, stretched vowels, big choruses and lyrics about council estates, Sunday roasts, slumming posh girls and being ‘caught by the fuzz’ filled the nation’s bedrooms.

It was, for about three years, marvellous. There was a genuine sense of optimism. Youth was turning against the Conservative government. Working-class voices were not only being heard, it was fashionable to boast about the dirt under one’s fingernails and the greasy spoon cafés one liked to frequent. Things were perhaps helped by the drugs of choice – ecstacy and cocaine – conducive to bonhomie on the one hand and confidence on the other.

Things were perhaps helped

by the drugs of choice – ecstacy and cocaine – conducive to bonhomie on the one hand and confidence on the other.

The sense of Britpop being a fightback against America reassured those worried about chauvinistic undertones. The supplanting of manufactured pop such as Take That and East 17 made Britpop’s rise feel subversive and revolutionary, channeling the spirit of both punk and the Sixties.

So many of its musical moments were sublime. Suede’s Animal Nitrate, Blur’s Girls and Boys, Elastica’s Connected, Pulp’s Common People, Oasis’s Live Forever, The Manics’ A Design For Life and The Verve’s Bittersweet Symphony are among the finest pop singles ever released by British acts. It seemed as though there were great new bands emerging every week. Even the Britpop second division – Supergrass, Sleeper, Kula Shaker, St Etienne, The Boo Radleys, Black Grape, Ocean Colour Scene, Cast, Shed Seven and the Bluetones – had their moments. We’d had to listen to our parents banging on about how amazing the Sixties were, but now we had our own version. It was a very good time to be young and British. Everything felt possible.

We should have noticed the signs. Was Blur’s Parklife really a celebration of the working-class or was it mockery? Why did Oasis think anyone who read a book was beneath contempt? Why was the high tide of Britpop considered to be England’s 1996 World Cup bid and not Scotland’s? Why was Chris Evans on TFI Friday always boasting about how much money he had? Why was Irvine Welsh’s scabrous, furious, punk novel Trainspotting given a glossy makeover and hip, London-friendly soundtrack? How had everything become so ironic? As Britpop’s commericial status rose its political subtext faded and reactionary forces took hold. The real clue was in the title: Brit signifying imperialism, pop meaning superficiality. A toxic mix. Its empire grew the way British empires do.

The sexual ambiguity of Suede became drowned out by the laddish roar of Oasis and the Essex boy poses of Damon Albarn. The frontwomen of the day, Sleeper’s Louise Wener and Elastica’s Justine Frischmann, disdained feminism. The Union Jack was stripped of its imperialist history and turned into a marketing tool. Where Definitely Maybe brimmed with the energy of the ‘outcasts, the underclass’, the definition of the proletariat that the Gallaghers came to define was based around simply being ‘mad for it’.

The Britpop politic was revealed as nothing more sophisticated than: get off your face and have a good time, all of the time. Frat-boy comedies have as much depth.

The Britpop politic was revealed as nothing more sophisticated than: get off your face and have a good time, all of the time. Frat-boy comedies have as much depth. ‘Political correctness’ started appearing in contemptuous finger quotes for the first time, the disregard for notions of equality implied. Unsurprisingly, there were no black or Asian Britpop icons. It was all, in short, highly congruent with Thatcherism, and, ultimately, New Labour.

The contradiction which would unravel Britpop was inherent in it from the start. All of its chief architects – Brett, Noel, Damon, Justine and Jarvis – craved mainstream success. In order to realise its aim of national togetherness, which it did with Oasis’s colossal Knebworth gigs in 1996, Britpop had to reach beyond the Halls of Residence and indie discos to the football terraces, teeny-bopper magazines and the BMWs of City boys. This brings immediate problems of nuance. By 1997, the year of Oasis’s overblown Be Here Now and Tony Blair’s co-opting of it all into the brand strategy ‘Cool Brittania’, the whole thing was revealed a monstrous, ego-fuelled charade which had almost nothing to do with class anymore. How very New Labour.

With Blair’s electoral ascent, the game was up. He’d taken the mood and turned it into a party which represented nothing. Each band was soon done-in by their own hedonism. Witness the array of drugs with which they destroyed themselves. For Suede it was crack, for Oasis cocaine, for Elastica heroin, for Blur alcohol, and for Pulp it was fame. This Is Hardcore, Pulp’s hangover album, compares the dehumanising effects of celebrity to those of porn. On Blur’s 13 Damon Albarn sounds shattered and heartbroken. Radiohead’s visionary OK Computer, which suggests that, actually, we’d been duped by a soulless mulch of consumerism all along, was the final knell. Only at Britpop’s death, then, did they think to drop the irony. We’re now living through what it masked all along.

But for a while there? Oh, it felt glorious. It really, really, really did happen.

Good article. While not as big as Pulp, Suede etc both Echobelly and Republica were fronted by non-white females.