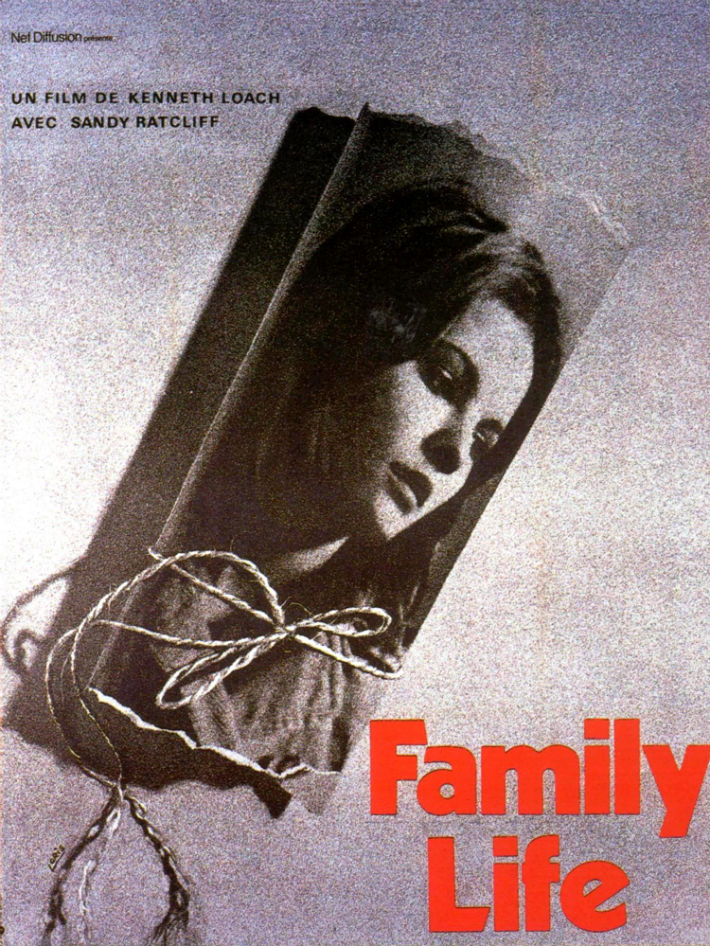

Very pleased to welcome music journalist and all-round musical and cultural obsessive, Brian Beadie, to the RR fold. Read this superb preview piece on Family Life, a film by Ken Loach, which screens in Glasgow on Tuesday 18th March. It sounds excellent.

RD Laing was one of the most influential, and charismatic figures to emerge on the Scottish cultural scene in the 1960s. His most famous books, The Divided Self and Knots sat on the bookshelves of every self-respecting would-be intellectual radical in the 60s and 70s. Yet his complete deconstruction of the barrier between doctor and patient in the patriarchal, authoritarian 60s would unnerve as many doctors as it would inspire free thinkers. In those times of intellectual free for all, where everything was up for grabs, madness was even briefly fashionable amongst the counter culture cognoscenti, who agreed with Laing that it could be the ultimate form of rebellion in a world that was, in itself, highly irrational and unjust.

Like his Viennese precursor Freud, his ideas would go on to influence many in the arts, leading to a kind of pop celebrity for their psychiatrist himself, who would record an album and live something of a rock star life, with a lot of booze and womanising along the way. Ultimately, though, all this would make it easier for the establishment to discredit him and marginalise his ideas. However, there has been a recent revival of interest in his work, evinced by theatrical adaptations of Knots and Luke Fowler’s remarkable Turner Prize nominated film about his life, All Divided Selves.

One of his most controversial ideas, set out in his book, Sanity, Madness and the Family, was that schizophrenia was a natural response to the pressures and demands of family life. This idea would have a major impact on another influential, largely forgotten figure of the period, David Mercer. If Mercer is remembered today, it is probably chiefly for his screenplay for Alain Resnais’ majestic Providence, a film that has inspired filmmakers as diverse as Peter Greenaway and Charlie Kaufman. Back in the swinging sixties, Mercer, a working class boy who got his break in TV drama, was best known for Morgan, A Suitable Case For Treatment, a hip cult comedy that mixed Marx and King Kong with Laing’s theories of schizophrenia, and was a favourite film of Malcolm McLaren.

His most serious examination of Laing’s ideas would come with In Two Minds, a TV play on which Laing would act as consultant. Like Morgan, In Two Minds would subsequently be remade as a film, Family Life, which is, perhaps unusually, even bleaker and more pessimistic than its TV original. Family Life is a significant film for many reasons. For a start, it was the only one of Ken Loach’s TV plays which he would remake for the cinema. While this would obviously give the film greater international exposure, and win it the Fipresci Prize at the Berlin Film Festival, this would also suggest Loach’s deep personal investment in the subject matter.

In those times of intellectual free for all, where everything was up for grabs, madness was even briefly fashionable amongst the counter culture cognoscenti…

The film uses Laing’s ideas to tell the story of a young woman, Janice, living in a restrictive family in an oppressive working class environment. In a clinical style, we watch her mental disintegration at the hands of her parents, society and the medical establishment. The austere, detached style elicits the viewer to react with even more anger and sympathy to Janice’s dilemma. One such viewer was Luc Dardenne, who has commented, “I remember feeling indignation at Janice’s situation, and compassion and comradeship for her. I’ve never forgotten her name and I’ve always admired this film – its immediacy, urgency and freedom.”

Certainly, we can see here in the meshing of Laing’s, Mercer’s and Loach’s ideas, an individual’s entrapment within society defined as precisely and unsentimentally as Billy Casper’s fate in Loach’s much better known film, Kes.

Ultimately, the question most will ask is how relevant is Laing to the early 21st century? Perhaps the real question should be: How would Janice fare now? While the psychiatric establishment certainly is more humane, it seems to be dictated by the profits of drug companies. And with the doors of the BBC closed to people of Loach’s and Mercer’s social and intellectual backgrounds, there are far fewer people willing and so eloquently capable of showing the plight of the disenfranchised.

Family Life screens at the GFT on Tuesday 18th March as part of KILTR Film Club. And on the night, Brian, who wrote this piece will be speaking to Tom Leonard about RD Laing and the film. Should be a good one.