Part Two of Stuart Cosgrove’s analysis of the Zoot-Suit and it’s perception and place in the socio-political history of the United States of America.

Part One if you haven’t read it yet is here.

As Joan W. Moore implies in Homeboys, her definitive study of Los Angeles youth gangs, the concept of pachuquismo is too readily and unproblematically equated with the better known concept of machismo (18). Undoubtedly, they share certain ideological traits, not least a swaggering and at times aggressive sense of power and bravado, but the two concepts derive from different sets of social definitions. Whereas machismo can be defined in terms of male power and sexuality, pachuquismo predominantly derives from ethnic, generational and class-based aspirations, and is less evidently a question of gender. What the Zoot-Suit Riots brought to the surface was the complexity of pachuco style. The Black Widows and their aggressive image confounded the pachuco stereotype of the lazy male delinquent who avoided conscription for a life of dandyism and petty crime, and reinforced radical readings of pachuco subculture. The Black Widows were a reminder that ethnic and generational alienation was a pressing social problem and an indication of the tensions that existed in minority, low-income communities.

Although detailed information on the role of girls within zoot-suit sub-culture is limited to very brief press reports, the appearance of female pachucos coincided with a dramatic rise in the delinquency rates among girls aged between 12 and 20 years old. The disintegration of traditional family relationships and the entry of young women into the labour force undoubtedly had an effect on the social roles and responsibilities of female adolescents, but it is difficult to be precise about the relationships between changed patterns of social experience and the rise in delinquency. However, war-time society brought about an increase in unprepared and irregular sexual intercourse, which in turn led to significant increases in the rates of abortion, illegitimate births and venereal diseases. Although statistics are difficult to trace, there are many indications that the war years saw a remarkable increase in the numbers of young women who were taken into social care or referred to penal institutions, as a result of the specific social problems they had to encounter.

The Zoot-Suit Riots had become a public and spectacular enactment of social disaffection. The authorities in Detroit chose to dismiss a Zoot-Suit Riot at the city’s Cooley High School as an adolescent imitation of the Los Angeles disturbances… Within three weeks Detroit was in the midst of the worst race riot in its history.

Later studies provide evidence that young women and girls were also heavily involved in the traffic and transaction of soft drugs. The pachuco sub-culture within the Los Angeles metropolitan area was directly associated with a widespread growth in the use of marijuana. It has been suggested that female zoot-suiters concealed quantities of drugs on their bodies, since they were less likely to be closely searched by male members of the law enforcement agencies. Unfortunately the absence of consistent or reliable information on the female gangs makes it particularly difficult to be certain about their status within the riots, or their place within traditions of feminine resistance. The Black Widows and Slick Chicks were spectacular in a sub-cultural sense, but their black drape jackets, tight skirts, fish net stockings and heavily emphasized make-up, were ridiculed in the press. The Black Widows clearly existed outside the orthodoxies of war-time society playing no part in the industrial war effort, and openly challenging conventional notions of feminine beauty and sexuality.

Towards the end of the second week of June, the riots in Los Angeles were dying out. Sporadic incidents broke out in other cities, particularly Detroit, New York and Philadelphia, where two members of Gene Krupa’s dance band were beaten up in a station for wearing the band’s zoot-suit costumes; but these, like the residual events in Los Angeles, were not taken seriously. The authorities failed to read the inarticulate warning signs proffered in two separate incidents in California: in one a zoot-suiter was arrested for throwing gasoline flares at a theatre; and in the second another was arrested for carrying a silver tomahawk. The Zoot-Suit Riots had become a public and spectacular enactment of social disaffection. The authorities in Detroit chose to dismiss a Zoot-Suit Riot at the city’s Cooley High School as an adolescent imitation of the Los Angeles disturbances.(19) Within three weeks Detroit was in the midst of the worst race riot in its history.(20) The United States was still involved in the war abroad when violent events on the home front signaled the beginnings of a new era in racial politics.

OFFICIAL FEARS OF FIFTH COLUMN FASHION

Official reactions to the Zoot-Suit Riots varied enormously. The most urgent problem that concerned California’s State Senators was the adverse effect that the events might have on the relationship between the United States and Mexico. This concern stemmed partly from the wish to preserve good international relations, but rather more from the significance of relations with Mexico for the economy of Southern California, as an item in the Los Angeles Times made clear.

In San Francisco Senator Downey declared that the riots may have “extremely grave consequences” in impairing relations between the United States and Mexico – and may endanger the program of importing Mexican labor to aid in harvesting California crops.(21) These fears were compounded when the Mexican Embassy formally drew the Zoot-Suit Riots to the attention of the State Department. It was the fear of an international incident (22) that could only have an adverse effect on California’s economy, rather than any real concern for the social conditions of the Mexican-American community; that motivated Governor Warren of California to order a public investigation into the causes of the riots. In an ambiguous press statement, the Governor hinted that the riots may have been instigated by outside or even foreign agitators:

As we love our country and the boys we are sending overseas to defend it, we are all duty bound to suppress every discordant activity which is designed to stir up international strife or adversely affect our relationships with our allies in the United Nations.(23)

The Zoot-Suit Riots provoked two related investigations – a fact finding investigative committee headed by Attorney General Robert Kenny and an un-American activities investigation presided over by State Senator Jack B Tenney. The un-American activities investigation was ordered “to determine whether the present Zoot-Suit Riots were sponsored by Nazi agencies attempting to spread disunity between the United States and Latin-American countries.”(24) Senator Tenney, a member of the un-American Activities committee for Los Angeles County, claimed he had evidence that the Zoot-Suit Riots were “axis-sponsored” but the evidence was never presented.(25)

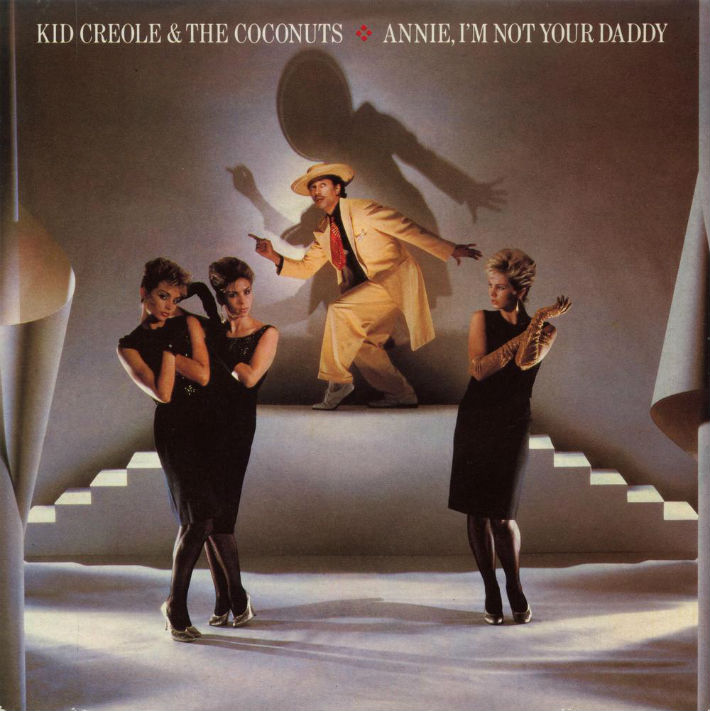

From the music of Thelonious Monk and Kid Creole to the jazz-poetry of Larry Neal, the zoot-suit has inherited new meanings and new mysteries.

However, the notion that the riots might have been initiated by outside agitators persisted throughout the month of June, and was fueled by Japanese propaganda broadcasts accusing the North American government of ignoring the brutality of US marines. The arguments of the un-American activities investigation were given a certain amount of credibility by a Mexican pastor based in Watts, who according to the press had been “a pretty rough customer himself, serving as a captain in Pancho Villa’s revolutionary army.”(26) Reverend Francisco Quintanilla, the pastor of the Mexican Methodist church, was convinced the riots were the result of fifth columnists. “When boys start attacking servicemen it means the enemy is right at home. It means they are being fed vicious propaganda by enemy agents who wish to stir up all the racial and class hatreds they can put their evil fingers on.”(27)

The attention given to the dubious claims of nazi-instigation tended to obfuscate other more credible opinions. Examination of the social conditions of pachuco youths tended to be marginalized in favour of other more ‘newsworthy’ angles. At no stage in the press coverage were the opinions of community workers or youth leaders sought, and so, ironically, the most progressal incident (22) that could or newspapers was offered by the Deputy Chief of Police, E.W. Lester. In press releases and on radio he provided a short history of gang subcultures in the Los Angeles area and then tried, albeit briefly, to place the riots in a social context.

The Deputy Chief said most of the youths came from overcrowded colorless homes that offered no opportunities for leisure-time activities. He said it is wrong to blame law enforcement agencies for the present situation, but that society as a whole must be charged with mishandling the problems.(28)

On the morning of Friday, 11 June 1943, The Los Angeles Times broke with its regular practices and printed an editorial appeal, “Time For Sanity” on its front page. The main purpose of the editorial was to dispel suggestions that the riots were racially motivated, and to challenge the growing opinion that white servicemen from the Southern States had actively colluded with the police in their vigilante campaign against the zoot-suiters.

There seems to be no simple or complete explanation for the growth of the grotesque gangs. Many reasons have been offered, some apparently valid. Some farfetched. But it does appear to be definitely established that any attempts at curbing the movement have had nothing whatever to do with race persecution, although some elements have loudly raised the cry of this very thing.(29)

A month later, the editorial of July’s issue of Crisis presented a diametrically opposed point of view:

These riots would not occur – no matter what the instant provocation – if the vast majority of the population, including more often than not the law enforcement officers and machinery, did not share in varying degrees the belief that Negroes are and must be kept second-class citizens.(30)

But this view got short shrift, particularly from the authorities, whose initial response to the riots was largely retributive. Emphasis was placed on arrest and punishment. The Los Angeles City Council considered a proposal from Councillor Norris Nelson, that “it be made a jail offense to wear zoot-suits with reat pleats within the city limits of LA”(31), and a discussion ensued for over an hour before it was resolved that the laws pertaining to rioting and disorderly conduct were sufficient to contain the zoot-suit threat. However, the council did encourage the War Production Board (WPB) to reiterate its regulations on the manufacture of suits. The regional office of the WPB based in San Francisco investigated tailors manufacturing in the area of men’s fashion and took steps “to curb illegal production of men’s clothing in violation of WPB limitation orders.”(32)

To wear a zoot-suit was to risk the repressive intolerance of wartime society and to invite the attention of the police, the parent generation and the uniformed members of the armed forces.

Only when Governor Warren’s fact-finding commission made its public recommendations did the political analysis of the riots go beyond the first principles of punishment and proscription. The recommendations called for a more responsible co-operation from the press; a program of special training for police officers working in multi-racial communities; additional detention centres; a juvenile forestry camp for youth under the age of 16; an increase in military and shore police; an increase in the youth facilities provided by the church; an increase in neighbourhood recreation facilities and an end to discrimination in the use of public facilities. In addition to these measures, the commission urged that arrests should be made without undue emphasis on members of minority groups and encouraged lawyers to protect the rights of youths arrested for participation in gang activity. Thc findings were a delicate balance of punishment and palliative; it made no significant mention of the social conditions of Mexican labourers and no recommendation about the kind of public spending that would be needed to alter the social experiences of pachuco youth. The outcome of the Zoot-Suit Riots was an inadequate. highly localized and relatively ineffective body of short term public policies that provided no guidelines for the more serious riots in Detroit and Harlem later in the same summer.

THE MYSTERY OF THE SIGNIFYING MONKEY

The pachuco is the prey of society, but instead of hiding he adorns himself to attract the hunter’s attention. Persecution redeems him and breaks his solitude: his salvation depends on him becoming part of the very society he appears to deny.(33)

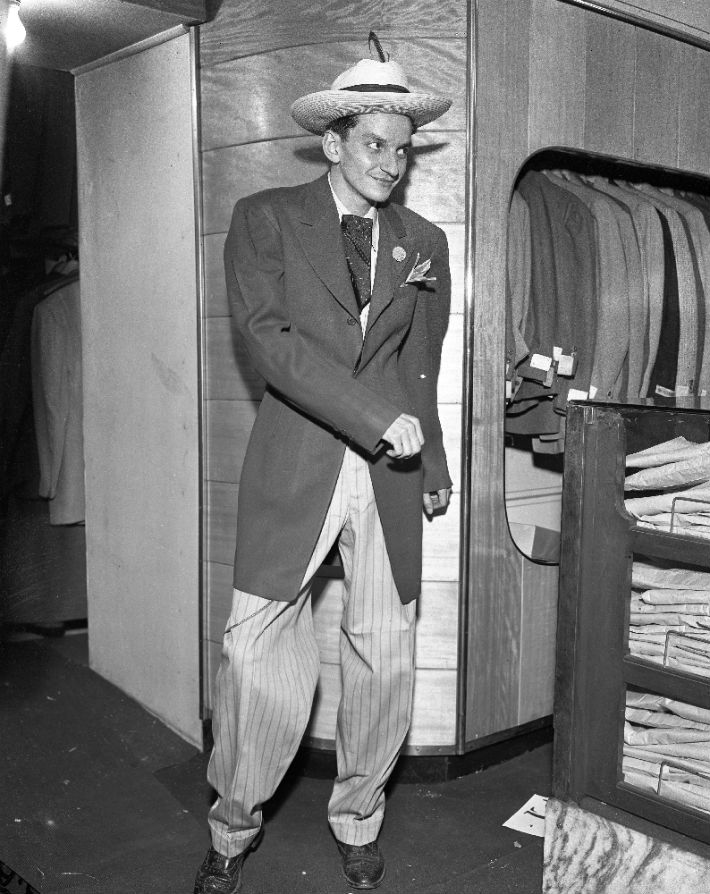

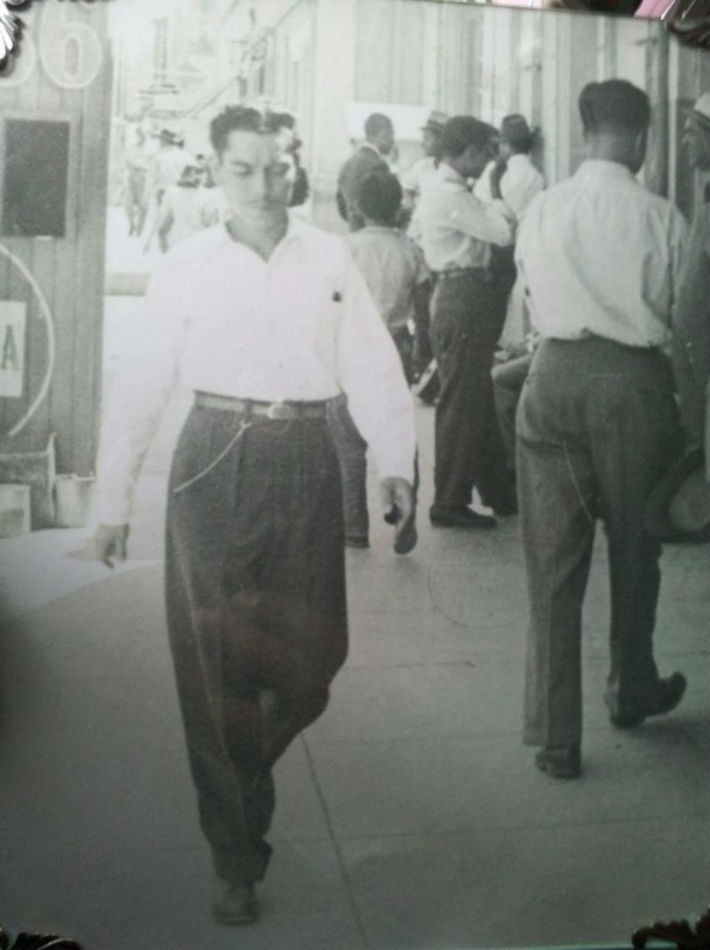

The zoot-suit was associated with a multiplicity of different traits and conditions. It was simultaneously the garb of the victim and the attacker, the persecutor and the persecuted, the “sinister clown” and the grotesque dandy. But the central opposition was between the style of the delinquent and that of the disinherited. To wear a zoot-suit was to risk the repressive intolerance of wartime society and to invite the attention of the police, the parent generation and the uniformed members of the armed forces. For many pachucos the Zoot-Suit Riots were simply high times in Los Angeles when momentarily they had control of the streets; for others it was a realization that they were outcasts in a society that was not of their making. For the black radical writer, Chester Himes, the riots in his neighbourhood were unambiguous: “Zoot Riots are Race Riots.”(34)

For other contemporary commentators the wearing of the zoot-suit could be anything from unconscious dandyism to a conscious ‘political’ engagement. The Zoot-Suit Riots were not political riots in the strictest sense, but for many participants they were an entry into the language of politics, an inarticulate rejection of the ‘straight world’ and its organization.

It is remarkable how many post-war activists were inspired by the zoot-suit disturbances. Luis Valdez of the radical theatre company, El Teatro Campesino allegedly learned the “chicano” from his cousin the zoot-suiter Billy Miranda.(35) The novelists Ralph Ellison and Richard Wright both conveyed a literary and political fascination with the power and potential of the zoot-suit. One of Ellison’s editorials for the journal Negro Quarterly expressed his own sense of frustration at the enigmatic attraction of zoot-suit style.

A third major problem, and one that is indispensable to the centralization and direction of power is that of learning the meaning of myths and symbols which abound among the Negro masses. For without this knowledge, leadership, no matter how correct its program, will fail. Much in Negro life remains a mystery; perhaps the zoot-suit conceals profound political meaning; perhaps the symmetrical frenzy of the Lindy-hop conceals clues to great potential powers, if only leaders could solve this riddle.(36)

Although Ellison’s remarks are undoubtedly compromised by their own mysterious idealism, he touches on the zoot-suit’s major source of interest. It is in everyday rituals that resistance can find natural and unconscious expression. In retrospect, the zoot-suit’s history can be seen as a point of intersection, between the related potential of ethnicity and politics on the one hand, and the pleasures of identity and difference on the other. It is the zoot-suit’s political and ethnic associations that have made it such a rich reference point for subsequent generations.

From the music of Thelonious Monk and Kid Creole to the jazz-poetry of Larry Neal, the zoot-suit has inherited new meanings and new mysteries. In his book Hoodoo Hollerin’ Bebop Ghosts, Neal uses the image of the zoot-suit as the symbol of Black America’s cultural resistance. For Neal, the zoot-suit ceased to be a costume and became a tapestry of meaning, where music. politics and social action merged. The zoot-suit became a symbol for the enigmas of Black culture and the mystery of the signifying monkey:

But there is rhythm here? Its own special substance? I hear Billie sing, No Good Man, and dig Prez, wearing the Zoot Suit of life, the Porkpie hat tilted at the correct angle; through the Harlem smoke of beer and whisky, I understand the mystery of the Signifying Monkey.(37)

//////

The author, Stuart Cosgrove, wishes to acknowledge the support of the British Academy for the research for this article.

18 Joan W Moore Homeboys: Gangs, Drugs and Prison in the Barrios of Los Angeles Philadelphia 1978

19 ‘Zoot Suit Warfare Spreads to Pupils of Detroit Area’ Washington Star 11 June 1943 p 1

20 Although the Detroit Race Riots of 1943 were not zoot-suit riots, nor evidently about ‘youth’ or ‘delinquency’, the social context in which they took place was obviously comparable. For a lengthy study of the Detroit riots see R Shogun and T Craig The Detroit Race Riot: a study in violence Philadelphia and New York 1964

21 ‘Zoot Suit War Inquiry Ordered by Governor’ Los Angeles Times 9 June 1943 p A

22 ‘Warren Orders Zoot Suit Quiz; Quiet Reigns After Rioting’ Los Angeles Times 10 June 1943 p 1

23 As note 22

24 ‘Tenney Feels Riots Caused by Nazi Move for Disunity’ Los Angeles Times 9 Junc 1943 p A

25 As note 24

26 ‘Watts Pastor Blames Riots on Fifth Column’ Los Angeles Times 11 June 1943 p A

27 As note 26

28 ‘California Governor Appeals for Quelling of Zoot Suit Riots’ Washington Star 1 June 1943 pA3

29 ‘Time for Sanity’ Los Angeles Times 11 June 1943 p 1

30 ‘The Riots’ The Crisis July 1943 p 199

31 ‘Ban on Freak Suits Studied by Councilmen’ Los Angeles Times 9 June 1943 p A3

33 Labyrinth of Solitude p 9

34 Chester Himes ‘Zoot Riots are Race Riots’ The Crisis July 1943; reprinted in Himes Black on Black: Baby Sister and Selected Writings London 1975

35 El Teatro Campesino presented the first Chicano play to achieve full commercial Broadway production. The play, written by Luis Valdez and entitled ‘Zoot Suit’ was a drama documentary on the Sleepy Lagoon murder and the events leading to the Los Angeles riots. (The Sleepy Lagoon murder of August 1942 resulted in 24 pachucos being indicted for conspiracy to murder.)

36 Quoted in Larry Neal ‘Ellison’s Zoot Suit’ in J Hersey (ed) Ralph Ellison: A Collection of Critical Essays New Jersey 1974 p 67

37 From Larry Neal’s poem ‘Malcolm X: an Autobiography’ in L Neal Hoodoo Hollerin’ Bebop Chosts Washington DC 1974 p 9

Pingback: Zoot-Suits & Style Warfare #1