Earlier in the year Neil Macdonald interviewed Laeitia Sadier. We thought we would share this with you on the run up to her forthcoming UK tour which includes a gig at Glasgow’s Broadcast venue on 6th Oct.

Laetitia Sadier founded Stereolab, with Tim Gane, way back in 1990, and for the next nineteen years (the group announced an ‘indefinite hiatus’ in 2009) helped introduce post-rock, krautrock, 60s European pop and experimental indie to countless enthusiastic pop-kids and moody musos alike via their beautiful, hypnotic, analogue future-pop.

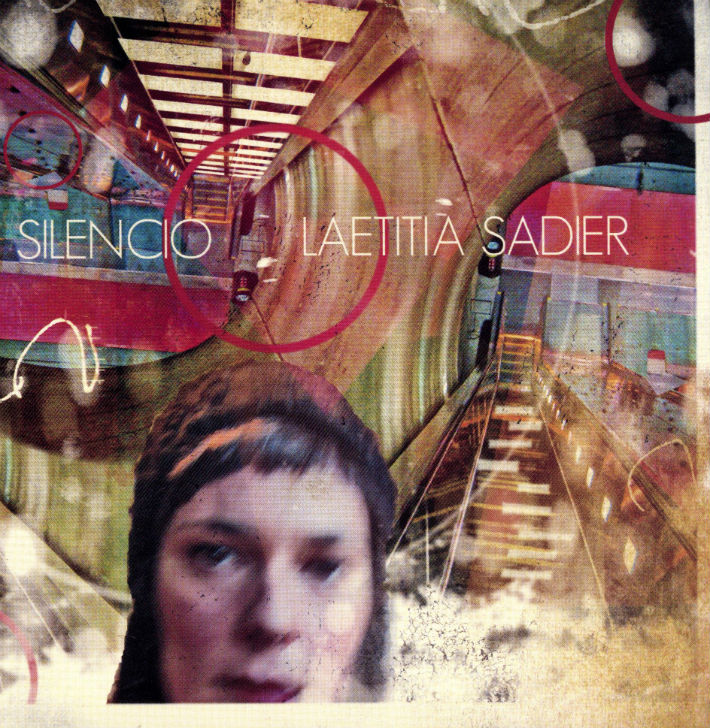

Modernist and vintage, sophisticated and shimmering, Stereolab – with their swirling grooves and motorik rhythms – were a very special band. When the band stopped, multi-instrumentalist and vocalist Laetitia carried on making music, and exactly the kind of music we would hope for, considering her role in the band. Following a short time with her own group – Monade – she’s now onto her second solo album and it was with some pleasure I were able to interview her. Silencio came out on July 24th, on Drag City. She plays at new Glasgow bar and music venue Broadcast on Tuesday 6th November as part of a short UK tour.

It almost seems like you’re working in reverse. You were in a band who owned their own label, and now you’re solo and signed to a label. Is it easier to create knowing that somebody else is looking after the business side of things, or does it feel like an obligation to create for somebody else?

I don’t know. That’s a tough question. Like “Why?” and “Who do I do this for?” I certainly don’t do this for a label. I don’t even know what force it is that makes me do things! I guess it’s a love of music, and wanting to express myself, but there’s an evolution. There are different reasons each time, I guess. With each record you’re somewhere different, and there are different motivations. It’s complex and almost paradoxical at the same time I guess, because when I write, I write for myself.

I write what I want to hear and what wants to come out, and I don’t worry about who’s going to hear it. I did wonder at some stage, I wondered what Tim would think – if it was corny or something! I’m freeing myself from that worry now, and it’s very liberating because he probably doesn’t care that much. If you start worrying about what people think, you won’t do it. There’s kind of this universal law of physics; there’s always going to be someone who likes it and someone who doesn’t. I don’t worry about it, but at the same time it’s about doing your best and showing your most authentic, sincere side. It’s about relevance, whether a personal relevance or a societal relevance. And those aren’t opposed. And I think that’s what my work is about.

I agree. Especially this record. Do you see Silencio as a statement? It seems to be your most political record.

It is my most political record. Auscultation to the Nation is the most overtly political track, and I didn’t even write those lyrics.

Yeah, what is that? A translation of some rant by somebody?

It was on a phone-in show. It’s a very political programme, and at the moment it really looks at the economy, and the forces of work within it. The stuff that you’re never going to hear on the news – it’s a big plot. Without being a conspiracy theorist.

Do you think the new French Socialist government is going to be an improvement?

No. No. They’re going to have to find a political way of explaining to people that their wages are going to be lowered. They support the system, they’re neo-liberalists. All their advisors are very dubious guys. No Marxists advisors. They want to carry on the system of debt, so that some financial markets can buy the debt and sell it on at a profit. It’s completely nuts. This government, the new Francois Hollande government, is in support of this system, and always has been. If people think they’re going to get a different system they’re wrong. They’re going to get more of this system, and maybe the differences will be played-out with, say, how aggressive the police are. And they’re very aggressive in France.

I voted against Sarkozy so that possibly my friends over there could avoid going through some very fascist and forceful things that people have to go through every day. Every day there would be enormous abuse of power under Sarkozy. It’s been like that for ten years, and Sarkozy’s been in power for ten years, because not only was he President for the last five, but he was also Minister of the Interior for five years before that, and they’re responsible for the police and such things. It was very clear under his rule how you ought to behave.

With that in mind, was this an album that you sat down to write, or is it songs that you’ve been inspired to write at different times?

It’s a funny question that, because at times I thought that I was sitting down to write an album, OK? It was in two batches. I sat down for four days between Christmas and New Year, and then there was another batch in February, for two weeks.

With each record you’re somewhere different, and there are different motivations. It’s complex and almost paradoxical at the same time I guess, because when I write, I write for myself.

That’s not long.

It wasn’t much time, but that was when I realised I’d been collecting ideas for months, and I went through them. Without me realising it, I’d throw them onto Photo Booth, on my Mac – where you can record yourself – and I had all these little ideas, so all I had to do was turn them into songs. And that was the actual work I did. Then there was a song I’d been working on for about two months, completely alone, and that became Merci de M’avoir Donné la Vie.

Does the available technology effect the creative process?

Hmmm. No. I think you still have to choose, and go with what you like. It’s a complicated question, because when you record now, you can record a whole song on a train…

So does that mean you end up with a greater body of work? Is there a massive editing process for you now?

No. That’s not how I operate. I have very little waste. I use most of what I do. I don’t have much lying about. I mean, I could write a song a day for a year and just keep the best ones for an album, but you see, I went to the Tim Gane school of music. He would only write what he needed to write. It’s not like I’ll write 75 songs, then work on 50, then record 35, and 25 will be on the record, two will be on the tour single, one will go there, two will go there… Conveyor belt. No.

Tell me about the near-silent track at the end of the album. Is that to separate the music from whatever else the listener hears next?

No, that’s not how it was intended. I intended to put the silent track inside the record, but somehow it did not want to go inside, it wanted to go at the end. That’s where it sounded best to me. Something I’ve learned, is that you might have an idea of something, and that idea might not work. If the idea doesn’t work you can’t force it. The track had to go where it wanted to go, because there’s a natural order, a natural configuration for things. There’s no use in being stubborn! The intention wasn’t to separate anything, but at the same time, it was to have a breather.

So it was intended more as a sonic element than as a psychological element?

Oh yes, very much.

Being able to re-arrange tracks sounds fun. Was it a fun record to make? It sounds like it was. Do you find it fun to make music? Is it easy for you?

Oh yes! I wouldn’t say it was easy, but it gets easier with experience. What gets easier is choosing the right people to work with. That makes the task much easier, if it is people who work with their hearts, and then you can have a synergy going on. The first batch of songs, the ‘Toulouse batch’, I did with some French brothers and sisters. Some brothers and sisters that it took a long, long, long time to meet. It was more of a band, so I was more of a kind of orchestrator. We did four songs in four days. I’d written the songs, but they weren’t necessarily arranged or anything. We didn’t mix them, but we recorded them. Which is quite an exploit. It really came together quickly, because they were listening to what I was saying, and understanding what I was saying! It was hard work, but it was pleasurable. And it went somewhere that we liked. The second batch we recorded in Chicago, at my friend James Elkington’s house, in his attic. He’s a Brit, actually. You know how the British are. They’re funny…

Well, I’m Scottish…

Well you are British. You’re not English, but you are British. Whether you like it or not. First of all you’re Scottish – I can hear that – and that’s the main thing, but you are British.

OK. That’s cool. So what about James then?

Well James is English. He’s not Scottish. But he’s really funny. We did have a really good laugh working together. It was fun to make and I’m glad that transpires.

Do you write music with certain musicians or engineers in mind? You’ve worked with some amazing people on your records. Like, say, Sam Prekop’s on this album. He’s got a very particular sound. Did you write parts knowing he’d be playing them?

No. No no no no no. You just write what you can. You write the song, then you see who’s available, and who’s willing. Then you have to ask people. I certainly don’t have a ‘final sound’ when I write a song, I don’t think it’s possible. Maybe for some people who are really technical or something, but for me: no. I may have particular ideas. I was listening to David Axelrod, and you know how his music is so sculpted? It’s not like “We”ll put the drums in, the bass in, the guitar in, the singing on top, and a bit of keyboard”, it’s like it’s made of vibes, and there’ll be a bass arriving, some strings arriving, and then BAH-BAH! Something else. And them maybe some crazy guitar. It’s sculpted. So I though, Oh, wow! I want to do something like that! y’know? And that’s how we started with Jim. It was track three, Silent Spot, and we just didn’t want to use a click track or anything. It’s very time-consuming to work like that, and I had twelve days to record seven tracks. It’s a lot of work, and a day isn’t very long when you’re recording a track.

To adopt an approach like that, do you find it an easier decision to make when you’re making a solo album?

Yes. With Stereolab I didn’t have anything to do with the music, which was incredibly frustrating! But it was clear – my territory was the lyrics and the singing. Full stop. Occasionally I’d be able to slip in a title or something. With Monade, it was my playground, it was my beginnings. My experimental ground. Some of it was solitary, some of it was with a group of friends. I think that what, today, really gives me the freedom to change my mind and to be myself is just the experience of Sterolab, the experience of Monade finally come to fruition whereby I can really listen to myself and have the confidence in what I create. Although it’s not necessarily ‘mine’ in the sense that I own it, but I can guide it. I have more experience to guide it.

In what way do you not own it? Is it because there’s a band of musicians working with you?

I had this sensation when I gave birth to my son – that I’m responsible for my child but I don’t own him. It’s the same with my songs. OK, they come out of me, I create them, but I don’t own them. The concept of ownership here, simply cannot apply. I’m responsible for them in that I have to make them as beautiful as I can on the record, and I have to go out and play them as well as I can, but I don’t own them. They’re not ‘mine’.

Do you have a favourite out of the people you’ve worked with? Anybody you’d especially like to work with?

I’d love to work with Jim again, I’d love to work with Richard Swift again, I’d love to work with my crew of lovely people in Toulouse again – they’re very talented, very hard working and not ashamed of their ideas. Yuuki Matthews… Sometimes I think of people and then I forget… I’d like to work with Phoenix. I’d like to work with Erykah Badu. I think I would learn a lot from her.

You worked with Common, didn’t you?

Yes, I did do. I did. I recorded the tape at home in London, and sent it to him wherever, so it was all done via labels. I did meet him once. He rang me up. I wish I had been more awake at the time. I didn’t like rap at the time, because I didn’t know the good stuff – I didn’t even know Common! But this guy was just so endearing, I couldn’t say no. It was only later that I discovered how good he is. I didn’t see that at the time. Silly me!

At least you still agreed to do the track!

Yeah, but it was only because it was so impossible to say no!

What about Nurse With Wound? Were you a fan of theirs before Stereolab collaborated with them?

Tim was. But I’m really a fan of that record we did together. I think it’s really, really super.

Do you listen to any of your own music for entertainment?

No. No. But, actually, yesterday I was in the car with a friend and he had (Stereolab compilation) Fab Four Suture, and we played that. And it was quite entertaining. Not all tracks, but some tracks. But I don’t. I should, because I’m so unaware of some of our records. Like, “What do they sound like with all this distance?” Not enough time!

Do you use much of your equipment from previous records on the new stuff? Some of it sounds familiar, some of it sounds totally alien.

Good! I like to hear that. The singing, I guess, will be reminiscent of Stereolab. But yeah, we use an iPad. The iPad Moog app. And that sounds like an instrument in its own right, like nothing else. Not even the Moog itself. So I was really pleased to find a sound that was absolutely new.

Did you use a real Moog at all? Any analogue electronics on this record?

No. Well, the stuff that Sam Prekop did was analogue electronics, although I couldn’t tell you any names. I don’t know what he’s got. All I know is that it’s analogue, and it sounds really cool. Haha!

Is a solo career a new era for you, or is it an evolution?

Well, there was the Stereolab era, and that subsided, then the Monade era, which subsided, so I can’t pretend it’s not a new era because it is. At the same time it’s a continuation. I don’t feel that there was a radical abandonment of the past. It happened very naturally, actually. I thought I had finished as a musician when the band finished, but then I realised I’d been building this body of work that was like a house that could house me, and house more work. And thanks to facebook I got invited to play in Belgium, in Greece, in Portugal, Brazil, Chile… All of a sudden people were like “Hey, you wanna come and play?” So I was like “OK! I’ll come and play. I’ll knock something together and come and play!”So it was circumstantial as well as natural. When I recorded The Trip, I mean I never thought I’d make a solo record, but the publishing company gave me some money and said “Record your new album”. I was like “What new album? Oh, a new album! OK!” Everything just fell into place. And I love it.

Have Stereolab officially split? It was called an ‘indefinite hiatus’ at the time – is that still the case?

It’s still an indefinite hiatus. But I’m not holding my breathe!

Sure, but it still isn’t an official split?

Tim’s too intelligent for that.

Does your son enjoy his parents’ music?

Ah, it’s a mystery. I think he secretly does.

And doesn’t admit it?

No!

Is there anything you’re listening to just now that you think fans of the music you do would like?

Ah… Shit… I’m listening to a beautiful record just now. It’s a record that everyone who comes to my house wants to listen to, and a record that just seduces everybody who hears it. It’s a record Elefant Records sent me, it’s by Giorgio Tuma and it’s called In The Morning We’ll Meet. It’s so poetic and it’s so beautiful. I like Emma Pollock, one of your fellow Scottish people. I listen her latest a lot, it’s called The Law of Large Numbers, and I’m sure she’ll have another one on the way. I’ve been listening to the new Thurston Moore record, which is nice. We swapped records with Thurston. I like to listen to this guy Benjamion Schoos a lot. It sounds very Gainsbourg. We did a song together in fact. Oh, I’m doing my own promo here!

Go for it, do your own promo!

It’s called ‘Je Ne Vois Que Vous’ and it’s super fun! It’s the perfect summer hit.

Nice. What are your plans for beyond the summer?

The album will be out, and we’ll be touring with it. I know that in America I’m putting together a three-piece band, and then I’ll be touring Europe either alone or with the three-piece band. I think the songs can stand the ‘alone’ thing. I could do it alone, or I could put together a three-piece for Europe, but it’s all about the people. I want my guts to say, “Yes! This person!” Rather than just doing it because it has to be done this way.

This interview first appeared on Neil’s Bite My Wire Blog. There’s loads of good stuff on there so it’s well worth a dig.