Stuart Cosgrove embarks on a historical evaulation and contextualisation of the famous Zoot-Suit. Part One of a crucial piece of pop culture writing.

INTRODUCTION: THE SILENT NOISE OF SINISTER CLOWNS

The zoot-suit is more than an exaggerated costume, more than a sartorial statement, it is the bearer of a complex and contradictory history.

What about those fellows waiting still and silent there on the platform, so still and silent they clash with the crowd in their very immobility, standing noisy in their very silence; harsh as a cry of terror in their quietness? What about these three boys, coming now along the platform, tall and slender, walking with swinging shoulders in their well-pressed, too-hot-for-summer suits, their collars high and tight about their necks, their identical hats of black cheap felt set upon the crowns of their heads with a severe formality above their conked hair?

It was as though I’d never seen their like before: walking slowly, their shoulders swaying, their legs swinging from their hips in trousers that ballooned upward from cuffs fitting snug about their ankles; their coats long and hip-tight with shoulders far too broad to be those of natural western men. These fellows whose bodies seemed – what had one of my teachers said of me? “You’re like one of those African sculptures, distorted in the interest of design”. Well, what design and whose? (1)

When the nameless narrator of Ellison’s Invisible Man confronted the subversive sight of three young and extravagantly dressed blacks, his reaction was one of fascination not of fear. These youths were not simply grotesque dandies parading the city’s secret underworld, they were “the stewards of something uncomfortable”(2), a spectacular reminder that the social order had failed to contain their energy and difference. The zoot-suit was more than the drape-shape of 1940s fashion, more than a colourful stage-prop hanging from the shoulders of Cab Calloway, it was, in the most direct and obvious ways, an emblem of ethnicity and a way of negotiating an identity. The zoot-suit was a refusal: a subcultural gesture that refused to concede to the manners of subservience. By the late 1930s, the term ‘zoot’ was in common circulation within urban jazz culture. Zoot meant something worn or performed in an extravagant style, and since many young blacks wore suits with outrageously padded shoulders and trousers that were fiercely tapered at the ankles, the term zoot-suit passed into everyday usage.

The zoot-suit was more than the drape-shape of 1940s fashion, more than a colourful stage-prop hanging from the shoulders of Cab Calloway, it was, in the most direct and obvious ways, an emblem of ethnicity and a way of negotiating an identity.

In the sub-cultural world of Harlem’s nightlife, the language of rhyming slang succinctly described the zoot-suit’s unmistakable style: a killer-diller coat with a drapeshape, real-pleats and shoulders padded like a lunatic’s cell. The study of the relationship between fashion and social action is notoriously underdeveloped, but there is every indication that the zoot-suit riots that erupted in the United States in the summer of 1943 had a profound effect on a whole generation of socially disadvantaged youths. It was during his period as a young zoot-suiter that the Chicano union activist Cesar Chavez first came into contact with community politics, and it was through the experiences of participating in zoot-suit riots in Harlem that the young pimp, Detroit Red began a political education that transformed him into the Black radical leader Malcolm X. Although the zoot-suit occupies an almost mythical place within the history of jazz music – its social and political importance has been virtually ignored. There can be no certainty about when, where or why the zoot-suit came into existence, but what is certain is that during the summer months of 1943 “the killer-diller coat” was the uniform of young rioters and the symbol of a moral panic about juvenile delinquency that was to intensify in the post-war period.

At the height of the Los Angeles riots of June 1943, the New York Times carried a front page article which claimed without reservation that the first zoot-suit had been purchased by a black bus worker, Clyde Duncan, from a tailor’s shop in Gainesville, Georgia.(3) Allegedly, Duncan had been inspired by the film Gone with the Wind and had set out to look like Rhett Butler. This explanation clearly found favour throughout the USA. The national press forwarded countless others. Some reports claimed that the zoot-suit was an invention of Harlem nigh’ life, others suggested it grew out of jazz culture and the exhibitionist stage costumes of the band leaders, and some argued that the zoot-suit was derived from military uniforms and imported from Britain. The alternative and independent press, particularly Crisis and Negro Quarterly, more convincingly argued that the zoot-suit was the product of a particular social context.(4) They emphasized the importance of Mexican-American youths, or pachucos, in the emergence of zoot-suit style and, in tentative ways, tried to relate their appearance on the streets to the concept of pachuquismo.

In his pioneering book, The Labyrinth of Solitude, the Mexican poet and social commentator Octavio Paz throws imaginative light on pachuco style and indirectly establishes a framework within which the zoot-suit can be understood. Paz’s study of the Mexican national consciousness examines the changes brought about by the movement of labour, particularly the generations of Mexicans who migrated northwards to the USA. This movement, and the new economic and social patterns it implies, has, according to Paz, forced young Mexican-Americans into an ambivalent experience between two cultures.

What distinguishes them, I think, is their furtive, restless air: they act like persons who are wearing disguises, who are afraid of a stranger’s look because it could strip them and leave them stark naked… This spiritual condition or lack of a spirit, has given birth to a type known as the pachuco. The pachucos are youths, for the most part of Mexican origin, who form gangs in southern cities; they can be identified by their language and behaviour as well as by the clothing they affect. They are instinctive rebels, and North American racism has vented its wrath on them more than once. But the pachucos do not attempt to vindicate their race or the nationality of their forebears. Their attitude reveals an obstinate, almost fanatical will-to-be, but this will affirms nothing specific except their determination… not to be like those around them.(5)

The pachucos are youths, for the most part of Mexican origin, who form gangs in southern cities; they can be identified by their language and behaviour as well as by the clothing they affect. They are instinctive rebels, and North American racism has vented its wrath on them more than once.

Pachuco youth embodied all the characteristics of second generation working-class immigrants. In the most obvious ways they had been stripped of their customs, beliefs and language. The pachucos were a disinherited generation within a disadvantaged sector of North American society; and predictably their experiences in education, welfare and employment alienated them from the aspirations of their parents and the dominant assumptions of the society in which they lived. The pachuco subculture was defined not only by ostentatious fashion, but by petty crime, delinquency and drug-taking. Rather than disguise their alienation or efface their hostility to the dominant society, the pachucos adopted an arrogant posture. They flaunted their difference, and the zoot-suit became the means by which that difference was announced. Those “impassive and sinister clowns” whose purpose was ‘to cause terror instead of laughter,'(6) invited the kind of attention that led to both prestige and persecution. For Octavio Paz the pachuco’s appropriation of the zoot-suit was an admission of the ambivalent place he occupied. It is the only way he can establish a more vital relationship with the society he is antagonizing. As a victim he can occupy a place in the world that previously ignored him; as a delinquent, he can become one of its wicked heroes.(7) The Zoot-Suit Riots of 1943 encapsulated this paradox. They emerged out of the dialectics of delinquency and persecution, during a period in which American society was undergoing profound structural change.

The major social change brought about by the United States’ involvement in the war was the recruitment to the armed forces of over four million civilians and the entrance of over five million women into the war-time labour force. The rapid increase in military recruitment and the radical shift in the composition of the labour force led in turn to changes in family life, particularly the erosion of parental control and authority. The large scale and prolonged separation of millions of families precipitated an unprecedented increase in the rate of juvenile crime and delinquency.

By the summer of 1943 it was commonplace for teenagers to be left to their own initiatives whilst their parents were either on active military service or involved in war work. The increase in night work compounded the problem. With their parents or guardians working unsocial hours, it became possible for many more young people to gather late into the night at major urban centers or simply on the street corners. The rate of social mobility intensified during the period of the Zoot-Suit Riots. With over 15 million civilians and 12 million military personnel on the move throughout the country, there was a corresponding increase in vagrancy. Petty crimes became more difficult to detect and control, itinerants became increasingly common, and social transience put unforeseen pressure on housing and welfare. The new patterns of social mobility also led to congestion in military and industrial areas. Significantly, it was the overcrowded military towns along the Pacific coast and the industrial towns of Detroit, Pittsburgh and LA that witnessed the most violent outbreaks of Zoot-Suit Rioting.(8)

‘Delinquency’ emerged from the dictionary of new sociology to become an everyday term, as wartime statistics revealed these new patterns of adolescent behaviour. The pachucos of the Los Angeles area were particularly vulnerable to the effects of war. Being neither Mexican nor American, the pachucos, like the black youths with whom they shared the zoot-suit style, simply did not fit. In their own terms they were “24-hour orphans”, having rejected the ideologies of their migrant parents. As the war furthered the dislocation of family relationships, the pachucos gravitated away from the home to the only place where their status was visible, the streets and bars of the towns and cities. But if the pachucos laid themselves open to a life of delinquency and detention, they also asserted their distinct identity, with their own style of dress, their own way of life and a shared set of experiences.

THE ZOOT-SUIT RIOTS: LIBERTY, DISORDER AND THE FORBIDDEN

The Zoot-Suit Riots sharply revealed a polarization between two youth groups within wartime society: the gangs of predominantly black and Mexican youths who were at the forefront of the zoot-suit subculture, and the predominantly white American servicemen stationed along the Pacific coast. The riots invariably had racial and social resonances but the primary issue seems to have been patriotism and attitudes to the war. With the entry of the United States into the war in December 1941, the nation had to come to terms with the restrictions of rationing and the prospects of conscription. In March 1942, the War Production Board’s first rationing act had a direct effect on the manufacture of suits and all clothing containing wool. In an attempt to institute a 26% cut-back in the use of fabrics. The War Production Board drew up regulations for the wartime manufacture of what Esquire magazine called, “streamlined suits by Uncle Sam.”(9) The regulations effectively forbade the manufacture of zoot-suits and most legitimate tailoring companies ceased to manufacture or advertise any suits that fell outside the War Production Board’s guide lines. However, the demand for zoot-suits did not decline and a network of bootleg tailors based in Los Angeles and New York continued to manufacture the garments. Thus the polarization between servicemen and pachucos was immediately visible: the chino shirt and battledress were evidently uniforms of patriotism, whereas wearing a zoot-suit was a deliberate and public way of flouting the regulations of rationing.

The zoot-suit was a moral and social scandal in the eyes of the authorities, not simply because it was associated with petty crime and violence, but because it openly snubbed the laws of rationing. In the fragile harmony of wartime society, the zoo-suiters were, according to Octavio Paz, “a symbol of love and joy or of horror and loathing, an embodiment of liberty, of disorder, of the forbidden.”(10)

The zoot-suit was a moral and social scandal in the eyes of the authorities, not simply because it was associated with petty crime and violence, but because it openly snubbed the laws of rationing.

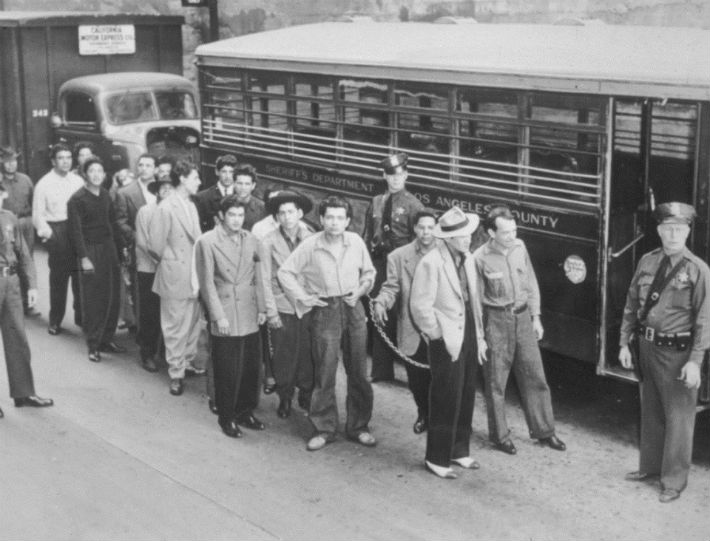

The Zoot-Suit Riots, which were initially confined to Los Angeles, began in the first few days of June 1943. During the first weekend of the month, over 60 zoot-suiters were arrested and charged at Los Angeles County jail, after violent and well publicized fights between servicemen on shore leave and gangs of Mexican-American youths. In order to prevent further outbreaks of fighting, the police patrolled the eastern sections of the city, as rumours spread from the military bases that servicemen were intending to form vigilante groups. The Washington Post’s report of the incidents, on the morning of Wednesday 9 June 1943, clearly saw the events from the point of view of the servicemen.

Disgusted with being robbed and beaten with tire irons, weighted ropes, belts and fists employed by overwhelming numbers of the youthful hoodlums, the uniformed men passed the word quietly among themselves and opened their campaign in force on Friday night.

At central jail, where spectators jammed the sidewalks and police made no efforts to halt auto loads of servicemen openly cruising in search of zoot-suiters, the youths streamed gladly into the sanctity of the cells after being snatched from bar rooms, pool halls and theaters and stripped of their attire. (11)

During the ensuing weeks of rioting, the ritualistic stripping of zoot-suiters became the major means by which the servicemen” re-established their status over the pachuco’s. It became commonplace for gangs of marines to ambush zoot-suiters, strip them down to their underwear and leave them helpless in the streets. In one particularly vicious incident, a gang of drunken sailors rampaged through a cinema after discovering two zoot-suiters. They dragged the pachuco’s onto the stage as the film was being screened, stripped them in front of the audience and as a final insult, urinated on the suits.

The press coverage of these incidents ranged from the careful and cautionary liberalism of The Los Angeles Times to the more hysterical hate-mongering of William Randolph Hearst’s west coast papers. Although the practice of stripping and publicly humiliating the zoot-suiters was not prompted by the press, several reports did little to discourage the attacks:

zoot-suits smouldered in the ashes of street bonfires where they had been tossed by grimly methodical tank forces of service men…

The zooters, who earlier in the day had spread boasts that they were organized to kill every cop they could find, showed no inclination to try to make good their boasts… Searching parties of soldiers, sailors and Marines hunted them out and drove them out into the open like bird dogs flushing quail. Procedure was standard: grab a zooter. Take off his pants and frock coat and tear them up or burn them. Trim the ‘Argentine Ducktail’ haircut that goes with the screwy costume.(12)

The second week of June witnessed the worst incidents of rioting and public disorder. A sailor was slashed and disfigured by a pachuco gang; a policeman was run down when he tried to question a car load of zoot-suiters; a young Mexican was stabbed at a party by drunken Marines; a trainload of sailors were stoned by pachuco’s as their train approached Long Beach; streetfights broke out daily in San Bernardino; over 400 vigilantes toured the streets of San Diego looking for zoot-suiters, and many individuals from both factions were arrested.(13) On 9 June, the Los Angeles Times published the first in a series of editorials designed to reduce the level of violence, but which also tried to allay the growing concern about the racial character of the riots.

To preserve the peace and good name of the Los Angeles area, the strongest measures must be taken jointly by the police, the Sheriff’s office and Army and Navy authorities, to prevent any further outbreaks of ‘zoot suit’ rioting. While members of the armed forces received considerable provocation at the hands of the unidentified miscreants, such a situation cannot be cured by indiscriminate assault on every youth wearing a particular type of costume? It would not do, for a large number of reasons, to let the impression circulate in South America that persons of Spanish-American ancestry were being singled out for mistreatment in Southern California. And the incidents here were capable of being exaggerated to give that impression.(14)

THE CHIEF, THE BLACK WIDOWS AND THE TOMAHAWK KID

The pleas for tolerance from civic authorities and representatives of the church and state had no immediate effect, and the riots became more frequent and more violent. A zoot-suited youth was shot by a special police officer in Azusa, a gang of pachucos were arrested for rioting and carrying weapons in the Lincoln Heights area; 25 black zoot-suiters were arrested for wrecking an electric railway train in Watts, and 1000 additional police were drafted into East Los Angeles. The press coverage increasingly focused on the most “spectacular” incidents and began to identify leaders of zoot-suit style. On the morning of Thursday 10 June 1943, most newspapers carried photographs and reports on three notorious zoot-suit gang leaders. Of the thousands of pachucos that allegedly belonged to the hundreds of zoot-suit gangs in Los Angeles, the press singled out the arrests of Lewis D English, a 23-yearold-black, charged with felony and carrying a “16-inch razor sharp butcher knife” Frank H. Tellez, a 22-year-old Mexican held on vagrancy charges, and another Mexican, Luis ‘The Chief’ Verdusco (27 years of age), allegedly the leader of the Los Angeles pachuco’s.(15)

The arrests of English, Tellez and Verdusco seemed to confirm popular perceptions of the zoot-suiters widely expressed for weeks prior to the riots. Firstly, that the zoot-suit gangs were predominantly, but not exclusively, comprised of black and Mexican youths. Secondly, that many of the zoot-suiters were old enough to be in the armed forces but were either avoiding conscription or had been exempted on medical grounds. Finally, in the case of Frank Tellez, who was photographed wearing a pancake hat with a rear feather, that zoot-suit style was an expensive fashion often funded by theft and petty extortion. Tellez allegedly wore a colourful long drape coat that was “part of a $75 suit” and a pair of pegged trousers “very full at the knees and narrow at the cuffs” which were allegedly part of another suit. The caption of the Associated Press photograph indignantly added that “Tellez holds a medical discharge from the Army”.(16)

What newspaper reports tended to suppress was information on the Marines who were arrested for inciting riots, the existence of gangs of white American zoot-suiters, and the opinions of Mexican-American servicemen stationed in California, who were part of the war effort but who refused to take part in vigilante raids on pachuco hangouts.

The revelation that girls were active led to consistent press coverage of the activities of two female gangs: the Slick Chicks and the Black Widows. The latter gang took its name from the members’ distinctive dress of black zoot-suit jackets, short black skirts and black fish-net stockings.

As the Zoot-Suit Riots spread throughout California to cities in Texas and Arizona, a new dimension began to influence press coverage of the riots in Los Angeles. On a day when 125 zoot-suited youths clashed with Marines in Watts and armed police had to quell riots in Boyle Heights, the Los Angeles press concentrated on a razor attack on a local mother, Betty Morgan. What distinguished this incident from hundreds of comparable attacks was that the assailants were girls. The press related the incident to the arrest of Amelia Venegas, a woman zoot-suiter who was charged with carrying, and threatening to use, a brass knuckleduster. The revelation that girls were active within pachuco subculture led to consistent press coverage of the activities of two female gangs: the Slick Chicks and the Black Widows.(17) The latter gang took its name from the members’ distinctive dress, black zoot-suit jackets, short black skirts and black fish-net stockings. In retrospect the Black Widows, and their active part in the subcultural violence of the Zoot-Suit Riots, disturb conventional understandings of the concept of pachuquismo.

//////

Part Two of Zoot-Suits & Style Warfare can be found here.

The author, Stuart Cosgrove, wishes to acknowledge the support of the British Academy for the research for this article.

1 Ralph Ellison Invisible Man New York 1947 p 380

2 Invisible Man p 381

3 ‘Zoot Suit Originated in Georgia’ New York Times 11 June 1943 p 21

4 For the most extensive sociological study of the zoot-suit riots of 1943 see Ralph H Turner and Samuel J Surace ‘zoot Suiters and Mexicans: Symbols in Crowd Behaviour’ American Journal of Sociology 62 1956 pp 14-20

5 Octavio Paz The Labyrinth of Solitude London 1967 pp 5-6

6 Labyrinth of Solitude p 8

7 As note 6

8 See KL Nelson (ed) The Impact of War on Amencan Life New York 1971

9 OE Schoeffler and W Gale Esquire’s Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Men’s Fashion New York 1973 p 24

10 As note 6

11 ‘Zoot-suiters Again on the Prowl as Navy Holds Back Sailors’ Washington Post 9 June 1943 p 1

12 Quoted in S Menefee Assignment USA New York 1943 p 189

13 Details of the riots are taken from newspaper reports and press releases for the weeks in question, particularly from the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Washington Post, Washington Star and Time Magazine

14 ‘Strong Measures Must be Taken Against Rioting’ Los Angeles Times 9 June 1943 p 4

15 ‘Zoot-Suit Fighting Spreads On the Coast’ New York Times 10 June 1943 p 23 16As note 15

17 ‘Zoot-Girls Use Knife in Attack’ Los Angeles Times 11 June 1943 p 1

Pingback: The Zoot-Suit & Style Warfare #2